| Microlivestock - Little-Known Small Animals with a Promising Economic Future (b17mie) հղում աղբյուրինb17mie.htm |

| Part IV : Rodents |

|

|

23 Paca

Pacas (Agouti paca)1,2 are large, white-spotted, almost tailless rodents with the potential to become a source of protein for the American tropics. They are found in lowlands from Mexico to northern Argentina. The meat is white and is considered the best of all Latin American game meat. It is common in local markets and restaurants. Tasting like a combination of pork and chicken, it sells at higher prices than beef and is a regular item of diet in some areas. In Costa Rica, pace is served on special occasions such as weddings or baptisms. It has a higher fat content than the lean meat of agoutis, rabbits, and chickens, and has no gamy taste.

Paca has promise as a microlivestock. In several countries, Belize and Mexico for example, people already keep them in cages beside their homes and fatten them on kitchen scraps. In Costa Rica, some are bred on farms, under houses, and even in apartments. Research on raising paces in captivity is under way at the Universidad Nacional in Heredia, Costa Rica; at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Balboa, Panama (see page 196); and at the Instituto de Historia Natural in Tuxtla Gutierrez, Mexico. In Turrialba, Costa Rica, an entrepreneur is already breeding and raising pace commercially.

While the pace has potential as a food source, many problems still must be resolved before it can be recommended for mass rearing. If solved, however, this species would become an attractive microlivestock.

AREA OF POTENTIAL USE

The pace has potential for use throughout its vast geographical range in Latin America.

APPEARANCE AND SIZE

In general appearance, paces are somewhat like giant guinea pigs. The legs are short, the forefeet have four "fingers," and the hindfeet have five small, hooflike "toes." The feet are partially webbed and are adapted both for digging and for swimming. Pacas burrow with all four feet as well as their teeth; even large roots are no obstacle.

Adults weigh 6-14 kg, males being somewhat larger than females. Although they may become bulbously fat, paces remain "one of the fastest things on four feet. " From a standing start, even a fat specimen can jump at least 1 m off the ground. Pacas are also agile. However, their skin's epidermal layer is thin and fragile, and large strips may be ripped off as they rush headlong through spiky undergrowth. However, such wounds heal astonishingly fast - frequently within days.

Pacas are chocolate brown in colon The head is somewhat lighter in shade than the body, and the underparts are whitish or buff colored. There are usually four longitudinal rows of white spots that may merge into stripes along each side of the body. The fur is coarse, spiny, and slippery, and has no underwool. Each hair is stiff, relatively sharp, and very smooth, which makes paces extremely difficult for predators to hang on to.

Parts of the cheekbones are enlarged, and the cheeks can open to form special pouches. This is more developed in adult males than in females - indeed, adults can be readily sexed by head shape. The pouches are outside of the mouth and are fully haired. The animals use them mainly to create a resonating chamber for their booming bark and noisy tooth grinding. These enlarged cheeks push the large bulging eyes toward the top of the skull. The eyes are suited for nocturnal conditions, the senses of smell and hearing are uncannily acute, and there is an array of long whiskers that is used when maneuvering at night.

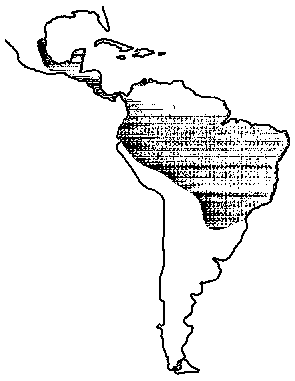

DISTRIBUTION

Lowland paces are found throughout most of Latin America from east central Mexico to northern Paraguay, Argentina, and Minas Gerais, Brazil. This includes all of Central America and most of Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Venezuela, and the Guianas. The animal has also been introduced into Cuba.

The paca’s native range

STATUS

Burgeoning human populations are severely reducing many of Latin America's native animal resources, and the pace is one of the most persecuted. It has been exterminated within hunting range of virtually all cities, towns, and villages.

Several governments, recognizing the pace's plight, have passed laws prohibiting the hunting and marketing of its meat. Nevertheless, people continue to take it, usually at night, using trail dogs and headlights.

HABITAT AND ENVIRONMENT

Pacas thrive in a variety of tropical habitats but are most common in forests, swamps, and partly cleared grazing lands. They inhabit most types of forests from deciduous woodland to rainforest. Usually, they stay near streams or rivers, but they often live where there is no permanent water. They are abundant only in little-disturbed forest areas. Although preferring low, dense tree cover, paces sometimes inhabit open rocky areas and farmland.

BIOLOGY

These herbivores feed mainly on fruits, young seedlings, and some seeds. However, when fruits are scarce they may switch to browsing leaves and roots. They probably sometimes eat large insects, and, on rare occasion, may perhaps eat small vertebrates. Captive paces, like many other "frugivores," seem to develop a protein deficiency and will eagerly eat meat scraps on occasion.

The young are usually born singly after a gestation period of 146 days. There are probably 2 births a year. Females have an estrous period that begins shortly after giving birth. If mating does not take place at this time, the female becomes unreceptive until after the 3-month (sometimes 4- to 6-month) lactation is over. The length of the estrous cycle is 30 days.

During daylight hours, paces seclude themselves in brushy cover, in or under fallen logs, or in extensive underground burrows. The burrows, which may be several meters long, are dug in moist soil or taken over from other animals; they are often in river banks, on slopes, among tree roots, or under rocks. Usually, several exits are provided, often being plugged with leaves as a disguise.

BEHAVIOR

In the wild, paces dig large holes and rummage about the forest floor at night, gnawing on fruits. Pairs inhabit a defended area, sometimes living together in the same burrow, sometimes not. Also, they usually travel alone, following paths that lead to feeding grounds and water. Individual home ranges are small (1-3 hectares).

Although paces are terrestrial, they enter water freely, they swim well, they copulate in water, and, when alarmed, they generally attempt to escape by swimming. They are also lively and playful; however, they can be exceedingly obstinate. Sometimes fighting among themselves becomes very savage. When angered they growl, sometimes noisily, and they can suddenly jump on aggressors, real or imagined, delivering frightful wounds with their chisel-like front teeth thrust forward like a spear.

USES

As noted, pace meat is tasty and brings high prices in the markets. It is considered a delicacy in fine restaurants and was served to Queen Elizabeth during her October 1985 visit to Belize. In Mexico, paces, like pigs, are usually boiled unskinned. Even the skin is then edible.

HUSBANDRY

If treated appropriately when young, paces become manageable. They undergo "imprinting," a characteristic of most species that have been domesticated. An imprinted pace becomes so tame that it seeks out human company, follows people around like an amiable dog and, if turned out of its cage, returns voluntarily. (To achieve this degree of tameness it is necessary to remove the animal from its mother at an early age.)

Although wild paces are almost entirely nocturnal, tame paces are more active during daylight hours.

Young or partly grown paces are commonly exhibited in zoos. They eat prodigious quantities of almost any vegetation and have been called, "a good substitute for a large garbage pail." Diets can include rolled oats, raw vegetables, bananas, apples, and bread. They probably need additional protein occasionally, and seem to appreciate some fat in their diet.

ADVANTAGES

If husbandry can be developed, the clamor for pace meat throughout tropical America would be a big economic incentive for farming these animals. The excellence and wide acceptance of the meat is an indication that pace farming would be taken up both in rural and urban areas and by many levels of society.

LIMITATIONS

Pacas can harbor human diseases, including leishmaniasis and Chagas' disease.

Apart from the project in Panama (see page 194), paces have bred only sporadically in captivity, with few offspring surviving. However, successes have been recorded in zoos in London, San Diego, and Washington, D.C., and in a research project in Tuxtla Gutierrez, Mexico. In Costa Rica, they are also reportedly breeding well, with a survival rate of 90 percent since 1982, and 80 percent of the females are reproducing.3

All adult paces can be aggressive and dangerous. Their powerful incisors can inflict serious wounds. (They can even rip through planks.) Intraspecific aggression is one of the most serious impediments to captive breeding.

Unlike the capybara, the pace not only has a long gestation but usually bears a single young. Thus, the output of a single breeding female may be, at best, two offspring per year (at least this is the expected production in the wild). This "slow" breeding is a limitation. In captivity, however, there is a possibility that it can be speeded up.4 The fact that paces bond together in pairs is a limitation. If every female has to be accompanied by a male, then many (otherwise unnecessary) males have to be fed and maintained.

Male paces are considered difficult to keep as household pets because they spray females (or human substitutes) with a mixture of urine and glandular secretions. This can occur several times a day. In addition, they have anal glands that produce a musky odor that some people find objectionable.

RESEARCH AND CONSERVATION NEEDS

Although paces are common in some areas over the vast region from Mexico to Argentina, they are little understood, even by zoologists. In fact, most data concerning this animal have come from interviews with local hunters. Intensive field work is needed to develop an understanding of the pace's biology, status, and habitat requirements.

The popularity of pace meat makes it urgent to start this work as well as to begin breeding paces on an organized basis. Such projects would lay the groundwork for preserving the species.

Particular research needs concern the following:

- Age structure and reproductive performance;

- Growth rates and feeding habits;

- Behavioral patterns in captivity;

- Nutritional requirements;

- Meat quality;

- Helminth and arthropod parasites;

- Role in transmitting or perpetuating diseases;

- Reproduction (such as external manifestations of estrus in females); and

- Genetic variations that would allow the selection of animals adapted to captivity and females that produce multiple offspring - twins, triplets, or more.

Ways must be found to introduce more than one female to each male without inciting aggression.