| Microlivestock - Little-Known Small Animals with a Promising Economic Future (b17mie) հղում աղբյուրինb17mie.htm |

| Part IV : Rodents |

|

|

21 Hutia

Hispaniolan Hutia

The first meat Christopher Columbus tasted in the New World was probably hutia, a rodent avidly hunted by the Carib Indians. Hutia bones have been unearthed from kitchen middens of pre-Columbian inhabitants of all the Greater Antilles. Indians carried live hutias on voyages possibly in a semidomestic state as a source of food. On some islands, hutias were so eagerly sought that their populations were destroyed long before Europeans arrived. Slaves in the cane fields also hunted hutias for food. The surviving species later suffered when forests were cleared and cats, dogs, mongooses, and other predators were introduced. Consequently, the majority of hutia species died out, and today most surviving members of the family (Capromyidae) are facing extinction. Human predation continues in some areas (for instance, in Jamaica) where the tradition of "coneyhunting" still endures in a few regions.

Hutias should be tested as possible microlivestock: success could create the incentive for their complete protection. The animals seem to take well to captivity. The Jamaican hutia is already overproducing in zoos, causing a local glut of animals. And hutias are, or were until recently, kept in barns by some people in Cuba, who fed them on banana and other vegetable waste and ate them regularly.'

POTENTIAL AREA OF USE

The Caribbean.

APPEARANCE AND SIZE

Hutias are broad-headed, short-legged, robust animals with small eyes and ears. The various species are from 20 to 60 cm long and weigh from 1 to 9 kg - a size range from that of a guinea pig to that of a small dog. They walk with a slow, waddling motion, but can hop quickly if frightened or pursued. They also climb well.

The 10 1iving species are all big enough to be candidates for microlivestock. The best known and easiest species to keep in captivity are the Cuban hutia (Capromys pilorides) and Jamaican hutia (Geocapromys brownii).

The Cuban hutia (also called hutia conga) is about 60 cm long, with coarse fur, a raccoon-shaped body, and a thick tail covered with sparse bristles. A forest dweller, it weighs up to 7 kg.

The short-tailed Jamaican hutia is smaller: it is 33-45 cm long and weighs up to 2.5 kg.

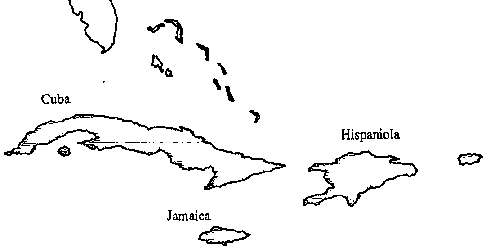

The hutia’s native range .

DISTRIBUTION

Hutias are found only in the Caribbean (Greater Antilles and Bahamas). Most species are confined to a single island, where they represent the only remaining indigenous land mammals. The Cuban hutia is found only in Cuba. The Jamaican hutia is found only in Jamaica, although a close relative occurs on East Plana Cay, Bahamas.

STATUS

This once widely distributed and plentiful family is now failing. Of the 30 or so known recent taxa, more than half are already extinct, and the remainder all suffer from habitat alteration, predation by introduced animals, and hunting by man. With the exception of the Cuban hutia, all species are included on the list of the world's threatened mammals.

HABITAT AND ENVIRONMENT

Hutia ranges have been so reduced that these animals survive only in the most inaccessible forests and rocky drylands. Both the Cuban and the Jamaican hutias occur in a variety of habitats from montane cloud forests to arid coastal semideserts.

BIOLOGY

Most species are terrestrial, but some live in trees. The Cuban and Jamaican species are terrestrial, but they can climb trees if circumstances demand. They maneuver well on trunks and larger branches, descending head first like squirrels.

Hutias are primarily vegetarian, their diets consisting of leaves, bark, fruits, and twigs, as well as incidental catches of small animals such as lizards and invertebrates.

Hutias seem to breed year-round, generally giving birth to litters of 1-4 offspring after a gestation period of 16-20 weeks. The young are well developed at birth, fully haired, open eyed, and capable of most adult movements. After 10 days they begin taking solid food, although they are not fully weaned for at least a month and a half (5 months for the Cuban hutia). Sexual maturity is at 10 months; life expectancy is 8-11 years in captivity.

The Jamaican hutia has one of the highest diploid chromosome numbers (2n = 88) of any mammal.

BEHAVIOR

Most hutias are wary and secretive and are easily displaced by human encroachment. They live like rabbits, hiding among tangled vegetation, in holes, and among rocks - communicating by voice and scent markings. They build shelters mainly in rock crevices, but also in the base of thick bushes or in natural cavities in trees. The Cuban hutia is often diurnal, whereas the Jamaican hutia is largely nocturnal.

HISPANIOLAN HUTIA

The Hispaniolan hutia, or zagouti (Plagiodontia aedium) as it is known in Haiti is smaller than the two Capromyids discussed here, weighing just 1.2 kg. It is difficult to breed in captivity and has a lower reproductive rate than either the Jamaican or Cuban hutia. It is therefore less suitable as an economic or food source.

However, there is a significant need for supplemental protein sources in both Haiti and the Dominican Republic. It might be possible to develop a special captive-breeding program for this animal, but it should be done with great care. It is important that a hunting tradition for this animal not be reestablished in rural areas of Haiti or the Dominican Republic, and that local organizations not be misled into believing that there will be a rapid increase in the numbers of this species in captivity.

USES

Hutia meat is relished, especially in Jamaica. The animals are still hunted, often by using dogs that smell them out and retrieve them from a hole or hold them at bay in treetops.

HUSBANDRY

Experiences of zoos suggest that the Cuban and Jamaican hutias will thrive in captivity. The animals are generally long-lived and have survived up to 17 years. They are often friendly with their keepers and, when tame, can be held and carried about without any particular danger. However, if angered they can inflict deep bites and should normally be handled with considerable caution.

ADVANTAGES

These animals are already much in demand. Their meat has an excellent flavor and they are big enough to provide a worthwhile quantity. If husbandry could be developed on a sustainable basis, it could be used as a mechanism for both economic development and for saving the remnant populations.

LIMITATIONS

Wild populations are threatened. Any captive population must be built up without endangering them.

All hutias are susceptible to predation by domestic cats, mongooses, dogs, and human poachers, so care must be taken to design predator-proof breeding facilities.

These animals are carriers of eastern equine encephalomyelitis, a serious disease of horses.

RESEARCH AND CONSERVATION NEEDS

Hutias deserve urgent conservation attention. In particular, the following steps should be taken:

- Establish reserves in natural habitats containing breeding populations to ensure the survival of the genetic diversity of these animals.

- Build up breeding populations in suitable zoos and livestock research centers.

- Gather specimens from different regions for comparative evaluation.

- Investigate hutia biology, including chromosome type, reproductive physiology, nutrition, and diseases.

- Assess experiences of zoos.

- Perform captive breeding trials, measuring growth rates, space requirements, food needs, and social behavior (both in its wild state and under controlled conditions).

- Study the social organization and tameability.

Colonies of some species could be established on uninhabited islands, as has been done with the Bahamian hutia Geocapromys ingrahami. Even this rare species might eventually be raised to yield meat for local inhabitants, as it is well adapted to dry and barren environments and was a regular food of the pre-Columbian Indians.