| Microlivestock - Little-Known Small Animals with a Promising Economic Future (b17mie) հղում աղբյուրինb17mie.htm |

| Part IV : Rodents |

|

|

18 Giant Rat

The giant rat, also known as the pouched rat, is one of Africa's largest rodents.! Two species have been distinguished: Cricetomys gambianus, which lives chiefly in savannas and around the edges of forests and human settlements; and Cricetomys emini, which occurs mainly in rainforests. Both are highly prized as food

These animals are solitary, but they are easy to handle, have a gentle nature, and make good pets. Researchers at the University of Ibadan in Nigeria have been developing techniques for managing them in captivity. Breeding stocks were established in 1973, and since then so many generations have been bred that this small population is considered domesticated. Commercial-scale giant rat farming is now being established in southern Nigeria.

This is a promising development because giant rats are a common "bushmeat" throughout much of Africa. Since these herbivores are well known there, and are acceptable as food, they may have as much or more potential as meat animals than the introduced rabbits that are getting considerable attention (see page 178).

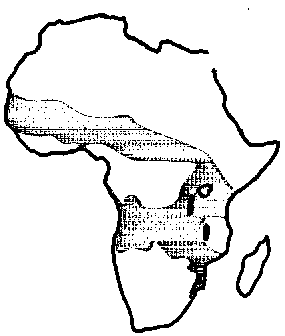

AREA OF POTENTIAL USE

The intertropical zone of Africa from the southern Sahara to the northern Transvaal.

APPEARANCE AND SIZE

This species is among the most striking of all African rodents.

Because of its large size, it often causes amazement - even alarm - when seen for the first time. The body measures as much as 40 cm, and, on average, weighs about 1-1.5 kg. The record for a hand-reared specimen is 1.6 kg 2

Apart from its size, the best known species (Cricetomys gambianus) is noted for the dark hair around its eyes, a nose that is sharply divided into dark upper and pale lower regions, and a tail that has a dark (proximal) section and pale (distal) section. The overall body color is a dusky gray.

The lesser known species (Cricetomys emini) has short, thin, and relatively sleek fur. Its upper parts are pale brown; the belly is white.

DISTRIBUTION

Giant rats are commonly found from Senegal to Sudan, and as far south as the northern region of South Africa. The main species is mostly found in moist savannas, patches of forests, and rainforests. However, it can also be found in all West African vegetation zones from the semiarid Sahel to the coast. It also exists at high altitudes— up to about 2,OOO m in West Africa and 3,000 m in eastern Africa.

The rainforest species occurs in the great equatorial forest belts of Zaire and neighboring Central African countries.

STATUS

These animals are probably not threatened with extinction. However, they have been exterminated in some areas (such as in parts of eastern Zaire) where the human population is dense, the land fully cultivated, and the wildlife overhunted. Although common, they are not as well known as one might suppose from their bulk and from the fact that they are sometimes found around, and even inside, houses.

HABITAT AND ENVIRONMENT

Giant rats occur largely in lightly wooded dryland regions or in forested humid regions. They cannot tolerate high temperatures or truly arid conditions. They often live in farm areas and in gardens. Their burrows are commonly found inside deserted termite mounds and at the base of trees. Some have also been found in the middle of cassava fields.

The giant rat’s distribution

BIOLOGY

These are herbivores with a tendency to omnivory. They prefer fruits, but also subsist on tubers, grains, vegetables, leaves, legume pods, and wastes (such as banana peels). However, they are not grasseaters. Giant rats also kill and eat mice, insects (caterpillars, cockroaches, and locusts, for example), and probably many other small animals.3 They are particularly fond of mollusks (such as snails).

Reproduction is prolific and year-round. The female attains puberty at 20-23 weeks and the gestation period is about 20-42 days. The young are weaned at 21-26 days of age but stay with their mother until 2-3 months of age. So far, the record for the most litters has been 5 in 9 months. It thus seems possible that a female can reproduce 6 times a year. Litter size ranges between I and 5, but 4 is most common. Thus, in 1 year a single female could produce 24 or more young.

BEHAVIOR

These strictly nocturnal animals usually lead solitary lives and forage alone. Mostly, they occupy a burrow by themselves, except when the

young are being raised. The burrows can be complex. Below the entrances are vertical shafts leading to a system of galleries and chambers for storing food, depositing droppings, sleeping, or breeding. The home range is individual and limited (1-6 hectares). In the wild, one male "supervises" the home ranges of several females.

In captivity, the animals are often seen sitting up and ramming large amounts of food into their spacious cheek pouches. With full cheeks, they return to their burrows and disgorge the food into a "larder." Food (chiefly hard nuts) is stored there.

They swim and climb well.

USES

A study carried out in Nigeria showed that the giant rat produces about the same amount of meat as the domestic rabbit.4 The meat's nutritional value compares favorably with that of domestic livestock, and African villagers know how to preserve it by smoking or by salting.

The giant rat has recently attracted attention as a potential laboratory animal.

HUSBANDRY

Farmers in Nigeria have traditionally trapped the juveniles and fattened them for slaughter. They usually keep the animals in wire cages and feed them daily with food gathered in the wild as well as with scraps from the household.

As noted, the program at the University of Ibadan indicates that the giant rat can be domesticated. Already, specimens are being bred and reared in an intensive program. They adapt to captivity after about a month. They are subsequently transferred into breeding cages, which are wooden boxes with a rectangular wire-mesh "playroom." Each cage holds a breeding pair or a nursing female with its young. Experimental feeding cages have also been designed.5

Food-preference trials show that palm fruits and root crops (especially sweet potato) are preferred to grains and vegetables. Nutritional studies show that the animals can tolerate up to 7 percent crude fiber in their rations. Although largely vegetarian, they eagerly consume dry and canned dog food.

ADVANTAGES

These animals have several advantages:

· They are well known and much sought after for food.

· They have adapted to life in lowland tropics.

· They are able to live on locally available plant materials, including vegetable waste.

· They reproduce rapidly.

· They are more tolerant of captivity than the grasscutter (see next chapter). This is largely because omnivorous feeding makes them easier to feed than the grasscutter and other strict herbivores.

LIMITATIONS

This species could easily become a pest. It is recommended for rearing only in areas where it already exists. The crops it damages include cacao, root crops, peanuts, maize, sorghum, vegetables, and stored grains and foods. There is also the possibility that this rodent may transmit diseases to humans.

A project at the University of Kinshasa in Zaire reports problems in getting giant rats to reproduce in captivity. When two specimens were paired they sometimes fought so viciously that copulation was impossible.6 Special management may be required, such as housing animals in adjacent cages before actually introducing them to each other. Moreover, selection for docility may also be necessary.

The ratlike appearance is not attractive, and a few African tribes have taboos against consuming the meat of these animals.

RESEARCH AND CONSERVATION NEEDS

Throughout Africa south of the Sahara, giant rat domestication deserves experimentation and trials. Success would open up the potential for supplemental meat supplies in rural and urban areas where meat is now scarce. Tests are needed to determine the factors that favor breeding: temperature, aeration, light, privacy, and size and form of cages. Moreover, diets that are cheap and easy to make from local feedstuffs must be identified.

Further research on the domestication of the giant rat might include:

· Identifying husbandry techniques that are applicable at low cost in rural areas;

· Studying food digestibility and setting up various diets;

· Illuminating social behavior: pairing of animals, the best moment for pairing, duration of pairing, age of partners;

· Outlining the basics of husbandry (for instance, capital costs, food conversion ratios, growth rates) and making simple and cheap cages;

· Studying biology (anatomy, physiology, birth records, growth rate); and

· Testing the practical likelihood that this rodent may transmit diseases to people and other animals.

The giant rat has an interesting commensal relationship with Hemimerus, an insect that feeds on secretions in the skin. It seems to cause no irritation or damage, and may even benefit the host by helping to keep the skin clean. Caging these animals results in the general loss of the insect, but attempts should be made to maintain them and to determine their role and life cycle.7

The potential of this species as a laboratory animal in nutritional, clinical, and pharmacological research also deserves exploration.