| Microlivestock - Little-Known Small Animals with a Promising Economic Future (b17mie) հղում աղբյուրինb17mie.htm |

| Part II : Poultry |

|

|

12 Turkey

FIGURE

The turkey (Meleagris gallopavo) is well-known in North America and Europe, but in the rest of the world, especially in developing countries, its potential has been largely overlooked. Partly, this is because chickens are so familiar and grow so well that there seems no reason to consider any other poultry. Partly, it is because modern turkeys have been so highly bred for intensive production that the resulting birds are inappropriate for home production.

Nevertheless, there is a much wider potential role for turkeys in the future. There are types that thrive as village birds or as scavengers, but these are little known even to turkey specialists. These primitive types are probably the least studied of all domestic fowl; little effort has been directed at increasing their productivity under free-ranging conditions. However, they retain their ancestral self-reliance and are widely used by farmers in Mexico. That they are unrecognized elsewhere is a serious oversight.

Native to North America, the turkey was domesticated by Indians about 400 BC, and today's Mexican birds seem to be direct descendants.' Unlike the large-breasted, modern commercial varieties, they mate naturally and they retain colored feathers and a narrow breast configuration. Their persistence in Mexico after 500 years of competition with other poultry highlights their adaptability, ruggedness, and usefulness to people.

These birds complement chicken production. They are able to thrive under more arid conditions, they tolerate heat better, they range farther, and they have higher quality meat. Also, the percentage of edible meat is much greater than that from a chicken. Turkey meat is so low in fat that in the United States, at least, it is making strong inroads into markets that previously used chicken exclusively.

Turkeys are natural foragers and can be kept as scavengers. Indeed, they thrive best where they can rove about, feeding on seeds, fresh grass, other herbage, and insects. As long as drinking water is available, they will return to their roost in the evening.

Appreciation for the turkey could rise rapidly. Interest already has been shown by several African nations. A French company has created a strain of self-reliant farm turkeys and is exporting them to developing countries.2 Researchers in Mexico are displaying increased interest in their national resource. And as knowledge and breeding stock continue to be developed, it is likely that village turkeys will become increasingly popular around the world.

AREA OF POTENTIAL USE

Worldwide.

APPEARANCE AND SIZE

Modern turkey breeding has been so dominated by selection for increased size and muscling that commercial turkeys have leg problems and cannot mate naturally (they are inseminated artificially). These highly bred birds are adapted for large-volume intensive production, and must be raised with care. As noted, this chapter emphasizes the more self-reliant, less highly selected turkeys found in Mexico and a few other Latin American countries. They do not require artificial insemination, and with little attention can care for themselves and their young.

Fully grown "criollo" turkeys of Mexico are less than half the size of some improved strains. Males weigh between 5 and 8 kg; females, between 3 and 4 kg.3 They vary in color from white, through splashed or mottled, to black. The skin of the neck and head is bare, rough, warty, and blue and red in color. A soft fleshy protuberance at the forehead (the snood) resembles a finger. In males it swells during courtship. The front of the neck is a pendant wattle. A bundle of long, coarse bristles (the beard) stands out prominently from the center of the breast.

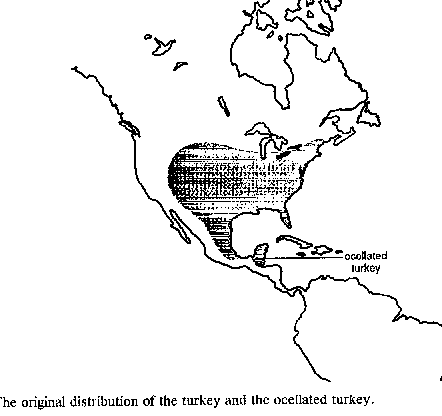

DISTRIBUTION

The unimproved domestic turkey is essentially limited to central Mexico and scattered locations throughout nearby Latin American countries. Some village birds are also kept in India, Egypt, and other areas, but these are descended from semi-improved strains exported from North America and Europe in earlier times. Generally speaking, few turkeys are found in tropical countries outside Latin America.

STATUS

Domesticated turkeys are not endangered; there are estimated to be about 124 million in the world. However, the wild Mexican varieties, ancestors to the first domesticated turkeys sent to Europe, may now be endangered since their distribution in southwestern Mexico has been greatly reduced. Certainly, some primitive domestic strains in the uplands of central Mexico are also being depleted. A separate type, independently domesticated by the Pueblo Indians of the southwestern United States, seems to have disappeared entirely.

HABITAT AND ENVIRONMENT

Turkeys can be reared virtually anywhere. Their natural habitat is open forest and wooded areas of the North American continent, but in Mexico they are raised from sea level to over 2,000 m altitude, from rainforest to desert, and from near-temperate climates to the tropics.

The original distribution of the turkey and the occellated

BIOLOGY

The range of diet is broad. Turkeys eat greens, fruits, seeds, nuts, grasses, berries, roots, insects (locusts, cicadas, crickets, and grasshoppers, for example), worms, slugs, and snails.

Reproduction is generally seasonal and is stimulated by increasing daylength. (A minimum daylength of 12 hours is required.) The birds can reach sexual maturity at six months of age and may start breeding at this time. Ten days after first mating, the hen searches out a nest and commences laying. Industrial birds in temperate climates lay, on average, 90 eggs a year. The nondescript type of turkey in the tropics seldom lays more than 20 small eggs (weighing about 60 am) before going broody.

BEHAVIOR

Domestic turkeys walk rather than fly, and find almost all their food on the ground. They can, however, fly short distances to avoid predators.

The commercial birds have lost many abilities for survival in the wild; they can no longer exist without human care. However, village types can do well with little management.

Turkeys prefer to make their own nests but can be induced to lay in a convenient spot if provided with nest boxes.

USES

These birds are raised almost exclusively for meat. In many countries, they are a treat for holidays, birthdays, and weddings. In their native range of Mexico and Central America, the "unimproved" birds are usually produced as a cash crop for market. They receive little care or feed, and thus they are almost all profit - providing a significant income supplement to many rural homes.

HUSBANDRY

The principles of turkey management (nutrition, housing, rearing' and prevention of disease, for example) are basically the same as those for other poultry.

In Mexico, turkeys are usually kept under free-ranging conditions around houses and villages. Some shelter and kitchen scraps are occasionally provided. A number of them, however, are confined in backyards as protection from marauders and for shelter against rain and wind.

One male can service up to 12 females. Roomy nests are needed. (As a rule, turkeys require three times the space occupied by chickens.) Most range turkeys are corralled when they begin to lay, so as to protect them from predators. Eggs may be gathered to prevent broodiness and thereby increase production. The eggs may be kept for several days (cool, but not refrigerated) if turned daily, and then may be placed under a chicken hen. (A setting chicken can be used this way to hatch up to nine eggs at a time.) Hatching takes 28 days.

As in other birds, newly hatched turkeys (poults) must be kept warm during the first weeks of life. Until they begin foraging and have full access to pasture they are usually fed broken grain or fine mash, as well as finely chopped, tender green feed.

Although free-ranging turkeys are simple to raise, confined turkeys require more complex management. The birds need uncrowded, well ventilated conditions and should be on a wire or slatted floor to reduce parasitic infections. Any feeds recommended for chicks are suitable, but the protein content should be somewhat higher; that is, about 27 percent. They can be fed mixed grains, corn, and chopped legume hay. It may be necessary to provide vitamin supplements and antibiotics and take steps to prevent coccidiosis.

"AN INCOMPARABLY FINER BIRD"

The turkey was domesticated in Mexico some time before the Conquest. It is the one and only important domestic animal of North American origin. When the Spanish arrived, they found barnyard turkeys in the possession of Indians in all parts of Mexico and even in Central America. However, the Aztecs and the Tarascans, originating in west-central Mexico, seemed to have achieved the highest development of turkey culture, and it is probable that turkeys were domesticated in the western highlands, perhaps in Michoacan. Wild turkeys of that region are morphologically very similar to the primitive domestic bronze type. Both the Aztecs and Tarascans kept great numbers of the birds, including even white ones. They paid royal tribute to their respective kings in turkeys, according to the Relacion de Michoacan. The Tarascan king fed turkeys to the hawks and eagles in his zoo. The economy of some highland tribes was based on the cultivation of corn and the raising of turkeys.

A. Starker Leopold

THE INDUSTRIAL TURKEY

The modern domesticated turkey is thought to be descended from two differing wild subspecies, one found in Mexico and Central America and the other in the United States. The southern type is small, whereas the U.S. native is larger and has a characteristic bronze plumage.

Mexican turkeys were exported to Europe soon after the Conquest, and spread rapidly. In the 17th century, some were returned to North America, where they interbred with the eastern subspecies of wild turkey, producing a heavier bird, which was then re-exported to Europe.

These types underwent little change until this century, when the Englishman Jesse Throssel bred them for meat quality. In the 1920s, he brought his improved birds to Canada, where their large size and broad breasts quickly made them foundation breeding stock. Crossed with the narrow-breasted North American types, these heavily muscled meat birds quickly supplanted other varieties.

About the same time, the U.S. Department of Agriculture began the scientific development of a smaller meat turkey derived from a more diverse genetic base. By the 1950s, the Beltsville Small Whites predominated in the home consumption market in the United States.

ADVANTAGES

The birds are efficient and generally take care of themselves. They tolerate dry, hot, or cold climates and forage farther than chickens. They are large, fast growing, highly marketable, low in fat, and tasty.

THE TURKEY'S TROPICAL COUSIN

The ocellated turkey (Agriocharis ocellata) occurs in Yucatan, Guatemala, and Belize. It is much like the common turkey in size, form, and behavior: however, unlike the common turkey, which in Mexico lives in the high mountain pine and oak forests, the ocellated turkey inhabits bushy, semiforested lowlands. This splendid bird lacks the kind of beard sported by the common turkey gobbler, is generally more metallic in appearance, and has brighter coppery colors. The chief character is a neck and head that are bare, blue, and profusely covered with coral-colored pimples. It also has a yellow-tipped protuberance growing on the crown between the eyes.

This species is worthy of investigation by poultry researchers because it might prove to be domesticable. It was possibly domesticated by the Mayas, whose ruins often include appropriately sized stone enclosures whose soil has elevated levels of phosphorus and potassium. Even today, in the rural Peten area of Guatemala, ocellated turkeys are sometimes kept around houses as scavengers.

LIMITATIONS

Young birds are readily affected by temperature changes and must be protected from the sun as well as from sudden chills, such as may occur at night. They are particularly susceptible to dampness, especially if associated with cold. One peculiarity is the turkey's aversion to any change in feeding routine or the nature of the food.

Young turkeys are susceptible to parasitic infestation as well as to the same type of bacterial and virus diseases as chickens (for example, fowlpox and coccidiosis). Blackhead, a devastating disease of young turkeys, is carried by a common parasitic nematode, and can be contracted from chickens. Medicines are available to prevent or treat most disease and pest problems.

RESEARCH AND CONSERVATION NEEDS

Turkey development is almost nonexistent in the Third World (and much of the rest of the world, too). Although commercial turkeys are highly developed in some countries, little or no research has been conducted on the criollo turkey. Research on physiology, disease, and husbandry of the criollo turkey should be given high priority.

The need for conservation of genetic variability is perhaps more critical in this species than in almost any other domesticated animal. The unimproved types in Mexico should be collected and assessed, and a program to conserve the stocks should be initiated. An analysis should also be made of the traditional management and performance of these birds. In addition, the four or five recognized turkey subspecies should be evaluated for their potential as seed stock for Third World countries.