| Microlivestock - Little-Known Small Animals with a Promising Economic Future (b17mie) հղում աղբյուրինb17mie.htm |

| Part II : Poultry |

|

|

11 Quail

FIGURE

Native to Asia and Europe, quail' (Coturnix coturnix2) have been farmed since ancient times, especially in the Far East. They reproduce rapidly and their rate of egg production is remarkable. They are also robust, disease resistant, and easy to keep, requiring only simple cages and equipment and little space. Yet they are not well known around the world and deserve wider testing.

Quail are so precocious that they can lay eggs when hardly more than 5 weeks old. It is said that about 20 of them are sufficient to keep an average family in eggs year-round. Quail eggs are very popular in Japan, where they are packed in thin plastic cases and sold fresh in many food stores. They are also boiled, shelled, and either canned or boxed like chicken eggs. Quail eggs are excellent as hors d'oeuvres and they also are used to make mayonnaise, cakes, and other prepared foods.

In France, Italy, the United States, and some countries in Latin America (Brazil and Chile, for example) as well as throughout Asia, it is the meat that is consumed. It is particularly delicious when charcoal broiled. One company in Spain annually processes 20 million quail for meat.

Many of the domesticated strains seem to have originated in China, and migrating Chinese carried them throughout Asia. Today, millions of domestic quail are reared in Japan, Indonesia, Thailand, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Indochina, Philippines, and Malaysia, as well as in Brazil and Chile.

Commercial production is carried out, as in the chicken industry, in specialized units involving hatcheries, farms, and factories that process eggs and meat. However, quail have outstanding potential for village and "backyard" production as well. It is this aspect that deserves greater attention.

AREA OF POTENTIAL USE

Worldwide.

APPEARANCE AND SIZE

Quail come in various sizes. The smaller types are used for egg production, whereas the larger ones are better for meat. Adult females of improved meat strains may weigh up to 500 g.

There are several color varieties. However, mature females are characterized by a tan-colored throat and breast, with black spots on the breast. Mature males, which are slightly smaller than females, have rusty-brown throats and breasts. All mature males have a bulbous structure, known as the foam gland, located at the upper edge of the vent.

In the United States, the Pharaoh strain is the bird of choice for commercial production. Other available strains tend to be bred more for fancy than for food.

Quail eggs are mottled brown, but some strains have been selected for white shells. These eggs are often preferred by consumers and are easier to candle (the process of holding eggs up to a light to check for interior quality and stage of incubation). An average egg weighs 10 g - about 8 percent of the female's body weight. (By comparison, a chicken egg weighs about 3 percent of the hen's body weight.) Quail chicks weigh merely 5-6 g when hatched and are normally covered in yellowish down with brown stripes.

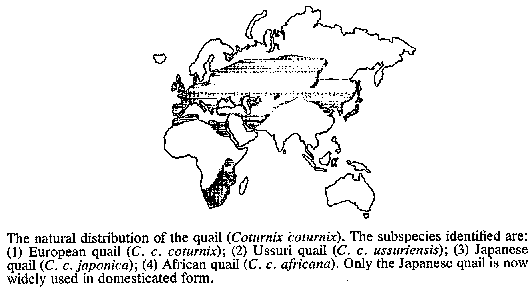

DISTRIBUTION

The ancestral wild species is widely distributed over much of Europe and Asia as well as parts of North Africa. Although domestic quail are now available almost everywhere, Japan is probably the world leader in commercial production; quail farms are common throughout its central and southern regions.

STATUS

Not endangered.

figure

HABITAT AND ENVIRONMENT

Quail are hardy birds that, within reasonable limits, can adapt to many different environments. However, they prefer temperate climates; the northern limit of their winter habitat is around 38ÝN.

BIOLOGY

A quail's diet in the wild consists of insects, grain, and various other seeds. To thrive and reproduce efficiently in captivity, it needs feeds that are relatively high in protein.

The females mature at about 5-6 weeks of age and usually come into full egg production by the age of 50 days. With proper care, they will lay 200-300 eggs per year, but at that rate they age quickly. The life span under domestic conditions can be up to 5 years. However, second-year egg production is normally less than half the first year's, and fertility and hatchability fall sharply after birds reach 6 months of age, even though egg and sperm production continue. Thus, the commercial life is only about a year.

Crosses between the wild and domestic stocks produce fertile hybrids. Repeated backcrossing to either wild quail or domestic quail is successful.

BEHAVIOR

Only females hatch the eggs and raise the chicks. Males go off and court other females when their partners begin the nesting process.

USES

Quail eggs taste like chicken eggs. They are often served hard boiled, pickled, fried, or scrambled. Because of their size they make attractive snacks or salad ingredients. They provide an alternative for some people who are allergic to chicken eggs. On frying, the yolk hardens before the albumen.

Quail meat is dark and can be prepared in all of the many ways used for chicken. The two meats are similar in taste, although quail is slightly gamier.

Because of its hardiness, small size, and short life cycle, quail are now commonly used as an experimental animal for biological research and for producing vaccines - especially the vaccine for Newcastle disease, to which quail are resistant.

Many fanciers and hobbyists have also become interested in raising this adaptable species as a pet. Science teachers find it an excellent subject for classroom projects.

QUAIL IN JAPAN

In some areas of Japan, quail are widely raised for their eggs and meat. However, Japanese originally valued the quail as a songbird. Tradition has it that about 600 years ago people began to enjoy its rhythmic call. In the feudal age, raising song quail became particularly popular among Samurai warriors. Contests were held to identify the most beautiful quail song and birds with the best voices were interbred in closed colonies. Even photostimulation was practiced to induce singing in winter.

Around 1910, enthusiastic breeders produced the present domestic Japanese quail from the song quail. It was created as a food source and became a part of Japanese cuisine. During World War II it was almost exterminated, but Japanese quail breeders restored it from the few survivors and from birds imported from China. The original song quail, however, were lost. In the 1960s, commercial quail flocks rapidly recovered and Japan's quail population again reached its prewar level of about 2 million birds.

A QUAIL IN EVERY POT: AN OLD DELICACY FINDS A NEW PUBLIC

For centuries, quail were considered a great delicacy: a dish that only eminent chefs would cook and diners with an appreciative palate could enjoy. These small migratory birds, which are found in one variety or another throughout the world, were available until recently almost exclusively to hunters in the wild.

But now quail are in danger: in danger of becoming commonplace.

In the last few years, quail have gone from being rarefied to a supermarket specialty item. They are on menus in the most elegant restaurants and the most casual cafes and bistros.

Why so much interest?

Quail are now available semi-boneless, which makes them faster and easier to cook, and easier to eat as well. The breastbones are removed by hand before the birds are packaged and shipped to stores. The bones in the wings and legs remain.

A stainless-steel V-shaped pin - invented and patented by a restaurant chef who wanted a way to keep quail flat for grilling— is inserted into the breast. The pin can be left there throughout cooking and removed just before serving.

While whole quail might require 45 minutes to cook, the semi-boneless variety can be grilled in less than 10 minutes, or pan-roasted, braised or sauteed in less than 20 minutes.

The flavor of farm-raised quail has also helped bring them into the mainstream. Most farm-raised quail have tender meat like the dark meat of chicken, whose flavor is enjoyed by many people.

And at a time when people are searching for foods, specifically animal protein, with low fat and cholesterol, quail fills the bill. The Agriculture Department says that quail skin has about 7 percent fat, about the same as dark meat of roasted chicken without the skin.

Judith Banrett Adapted from The New York Times

June 21, 1989

HUSBANDRY

It is necessary to keep quail in battery cages on wire floors because males secrete a sticky foam (from the foam gland) with their feces; on a solid floor, this adheres to the feet and collects dung, leading to crippling and breakage of eggs.

Adult quail can live and produce successfully if they are allowed 80 cm2 of floor space per bird. However, for reproduction about twice that is needed to allow for mating rituals.3 If properly mated, high fertility rates and good egg hatchability can be expected. To obtain fertile eggs, one male is needed for roughly six females.

Eggs hatch in about 17 days. Chicks require careful attention. Brooding temperatures of between 31 C and 35 C are needed for the first week and above 21 C for the second week. From the second week on, chicks can survive at room temperature. (These temperatures are similar to those required for common chickens.) In cold climates, supplemental heat may be needed as well as protection from cool drafts.

Clean water must be provided at all times, with care taken to prevent the chicks from drowning in their water troughs. Shallow trays, jar lids, or pans filled with marbles or stones may be used.

ADVANTAGES

Quail production can be started with little money. These easy-care birds can be housed in small, simple, inexpensive cages.

As noted, they are resistant to Newcastle disease.

SIX OF ONE, HALF A DOZEN OF THE OTHER

The fact that chickens can be crossed with quail has been known for some time, but there has been little attempt to develop the fertile hybrids. Now Malaysia has begun a project aimed at producing a new poultry bird - a cross between a cockerel and a hen quail. Zainal Abidin bin Mohd Noor, of the Department of Veterinary Services in Kuala Lumpur, is creating a strain that produces eggs of good quality and meat with the flavor of both parents. The new bird is intermediate in size between chicken and quail which is convenient because it is about right for an individual helping.

The crossbreeding is done through artificial insemination. The progeny exhibit a range of appearances, sizes, and plumage colors, depending on the strains of cockerel and quail hens used. In the Malaysian research, cockerels have been local Ayam Kampung Bantam, Hybro, and Golden Comet hybrids. The quails have been local inbred Japanese quail (IJQ) and imported meat strain quail (IMSQ).

The trials show that the hybrids derived from the IMSQ flocks grew faster and bigger than those from the IJQ cross. The best have been the Hybro x IMSQ crosses, which weigh 475 g at 10 weeks of age. The best of the IJQ group weighed 290 g during the same period.

This type of "tropical game hen" might be a way to introduce hybrid vigor into poultry production.

The researchers who developed the hybrid have named it the "yamyuh."

LIMITATIONS

Although generally disease resistant, quail are affected by several common poultry diseases, including salmonella, cholera, blackhead, and lice. They also suffer epidemic mortality from "quail disease" (ulcerative enteritis), which can, however, be controlled with antibiotics.

Quail seem to require more protein than chickens, and produce best when given feed that is fairly high in protein.4 However, they also perform satisfactorily when fed rations designed for turkeys. They have high requirements for vitamin A, which they do not store.

Quail are not suitable as free-ranging "scavengers." They must be kept confined, which is a major constraint. Unlike chickens or pigeons, they have no homing instinct and will not remain on a given site; if released, they will be lost. In addition, since they nest on the ground, they are highly susceptible to predation; they must be protected, especially where certain animals, the mongoose for example, are common.

Artificial incubation is essential. Natural incubation using the female is futile; the females do not go broody and rarely incubate their eggs. The shells are extremely thin, but the eggs can be incubated under a small chicken hen, such as a bantam.5 The eggs are also subject to minute fractures. However, the shell membrane is extremely tough and unfertilized eggs are generally unaffected, but the cracks cause fertilized embryos to dehydrate and die. This is a serious limitation. Whenever quail husbandry is introduced, artificial incubation should be included.

RESEARCH AND CONSERVATION NEEDS

Quail deserve to be included in all poultry research aimed at helping the Third World. Through its international scientific program, Japan, in particular, could apply to developing nations its vast experience with quail farming.

Experiences with quail in the tropics (for example, Japanese farmers in the Amazon Basin) and in tropical highlands (for instance, in India, Nepal, or Central Africa) should be collected and assessed to improve understanding of the environmental limits to Third World quail farming.

Cooperation between commercial and laboratory quail breeders should be encouraged. Mutants found at the commercial level would be useful for laboratory work. Conversely, introducing new stocks could help the farmer. In both cases, more genetic diversity might also lead to the production of hybrid vigor, and genetic variability would be conserved.

Sex-linked genes, if they can be found, would be useful to the commercial quail breeder for the rapid sexing of newly hatched chicks. This could lead to more efficient production techniques, like those in the chicken industry.

Although virtually all work to date has been on the Japanese quail, other species and subspecies warrant research and testing.