| Microlivestock - Little-Known Small Animals with a Promising Economic Future (b17mie) հղում աղբյուրինb17mie.htm |

| Part II : Poultry |

|

|

6 Ducks

FIGURE

Domestic ducks (Anas platyrhynchos)1 are well known, but still have much unrealized promise for subsistence-level production. Although a major resource of Asia, where there is approximately one duck per 20 inhabitants, they are not so intensively used elsewhere. On a worldwide basis, for instance, they are of minor importance compared with chickens.

This is unfortunate because ducks are easy to keep, adapt readily to a wide range of conditions (including small-farm culture), and require little investment. They are also easily managed under village conditions, particularly if a waterway is nearby, and appear to be more resistant to diseases and more adept at foraging than chickens.

Moreover, the products from ducks are in constant demand. Some breeds yield more eggs than the domestic chicken. And duck meat always sells at premium. A few recently created breeds (notably some in Taiwan) have much lower levels of fat than the traditional farm duck. This development could open up vast new markets for duck meat, especially in wealthy countries, where consumers are both concerned over fat in their diet and eager for alternatives to chicken.

Ducks are also efficient at converting waste resources - insects, weeds, aquatic plants, and fallen seeds, for instance - into meat and eggs. Indeed, they are among the most efficient of all food producers. Raised in confinement, ducks can convert 2.4-2.6 kg of concentrated feed into I kg of weight gain. The only domestic animal that has better feed conversion is the broiler chicken.

Raised as village birds and allowed to forage for themselves, ducks become less productive but become even more cost effective because much of the food they scavenge has no monetary value.

AREA OF POTENTIAL USE

Worldwide.

APPEARANCE AND SIZE

Several distinctive types have been developed in various regions. Most have lost the ability to fly any distance, but they retain a characteristic boatlike posture and a labored, waddling walk. The Indian Runner, however, has an almost erect stance that permits it to walk and run with apparent ease.

Domestic ducks range in body size from the diminutive Call, weighing less than I kg, to the largest meat strains (Pekin, Rouen, and Aylesbury, for example) weighing as much as 4.5 kg. For intensive conditions, the Pekin is the most popular meat breed around the world. In confinement it grows rapidly - weighing 2.5-3 kg at a market age of 78 weeks. In addition, it is hardy, does not fly, lays well, and produces good quality (but somewhat fatty) meat.

The Khaki Campbell breed is an outstanding egg producer, some individuals laying more than 300 eggs per bird per year.

The Taiwan Tsaiya (layer duck) is also a particularly efficient breed. It weighs 1.2 kg at maturity, starts laying at 120-140 days, and can produce 260-290 eggs a year. Its small body size, large egg weight, and phenomenal egg production make Brown Tsaiya the main breed for egg consumption in Taiwan. More than 2.5 million Brown Tsaiya ducks are raised annually for egg production.2

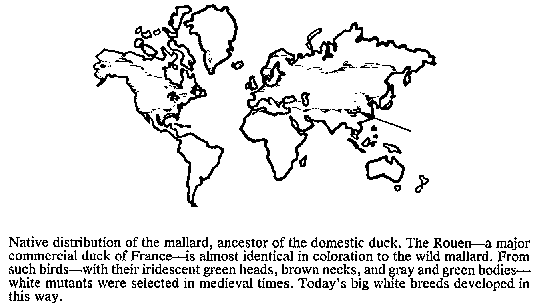

DISTRIBUTION

The domestic duck is distributed throughout the world; however, its greatest economic importance is in Southeast Asia, particularly in the wetland-rice areas. For example, about 28 percent of Taiwan's poultry are- ducks. In parts of Asia, some domestic flocks have as many as 20,000 birds. One farm near Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, rears 40,000 ducks.

STATUS

Although ducks are abundant, some Western breeds are becoming rare. Indigenous types are little known outside their home countries and have received little study, so their status is uncertain.

HABITAT AND ENVIRONMENT

These adaptable creatures thrive in hot, humid climates. However, during torrid weather they must have access to shade, drinking water, and bathing water.

Ducks are well adapted to rivers, canals, lakes, ponds, marshes, and other aquatic locations. Moreover, they can be raised successfully in estuarine areas. Most ocean bays and inlets teem with plant and animal life that ducks relish, but (unlike wild sea ducks) domestic breeds have a low physiological tolerance for salt and must be supplied with fresh drinking water.

BIOLOGY

Ducks search for food underwater, sieve organic matter from mud, root out morsels underground, and sometimes catch insects in the air. Their natural diet is normally about 90 percent vegetable matter (seeds, berries, fruits, nuts, bulbs, roots, succulent leaves, and grasses) and 10 percent animal matter (insects, snails, slugs, leeches, worms, eels, crustacea, and an occasional small fish or tadpole). They have little ability to utilize dietary fiber. Although they eat considerable quantities of tender grass, they are not true grazers (like geese), and don't eat coarse grasses and weeds at all. Sand and gravel is swallowed to serve as "grindstones" in the gizzard.

When protected from accidents and predation, ducks live a surprisingly long time. It is not unusual for one to continue reproducing for up to 8 years, and there are reports of exceptional birds living more than 20 years.

Despite large differences in size, color, and appearance, all domestic breeds interbreed freely. Eggs normally take 28 days to incubate, brooding and rearing is performed solely by the female.

Depending on breed, a female may reach sexual maturity at about 20 weeks of age. Most begin laying at 20-26 weeks, but the best egg- laying varieties come into production at 16-18 weeks and lay profitably for 2 years.

BEHAVIOR

It is generally well known that ducks are shy, nervous, and seldom aggressive towards each other or humans. Skilled and enthusiastic swimmers from the day they hatch, they spend many hours each day bathing and frolicking in any available water. However, most breeds can be raised successfully without swimming water.

Although wild ducks normally pair off, domestic drakes will mate indiscriminately with any females in a flock. In intensively raised flocks, I male to 6 females, and in village flocks, 1 male for up to 25 females, results in good fertility.

Most domestic ducks, particularly the egg-laying strains, have little instinct to brood. If not confined, they will lay eggs wherever they happen to be - occasionally even while swimming. To facilitate egg collection, some keepers confine ducks until noon.

Figure

USES

As a meat source, ducks have major advantages. Their growth rate is phenomenal during the first few weeks. (Acceptable market weights can be attained under intensive management with birds as young as 6-7 weeks of age.) Yet, even in older birds, the meat remains tender and palatable.

Eggs from many breeds are typically 20-35 percent larger than chicken eggs, weighing on average about 73 g. They are nutritious, have more fat and protein, and contain less water than hen's eggs. They are often used in cooking and make excellent custards and ice cream. Eggs incubated until just before the embryos form feathers produce a delicacy known as balut in the Philippines. Salted eggs are popular in China and Southeast Asia.

Feathers and down (an insulating undercoat of fine, fluffy feathers) are valuable by-products. Down is particularly sought as a filler for pillows, comforters, and winter clothing.

Ducks have a special fondness for mosquito and beetle larvae, grasshoppers, snails, slugs, and crustaceans, and therefore are effective pest control agents. China, in particular, uses ducks to reduce pests in rice fields.3 Its farmers also keep ducks to clear fields of scattered grain, to clear rice paddy banks of burrowing crabs, and to clear aquatic weeds and algae out of small lakes, ponds, and canals. This not only improves the conditions for aquaculture and agriculture, it also fattens the ducks.

HUSBANDRY

In Southeast Asia, droving is a traditional form of duck husbandry, much as it was in medieval Europe. The birds are herded along slowly, foraging in fields or riverbanks as they march to market. The journey might cover hundreds of kilometers and take as long as six months.

This process, however, is generally declining, and most ducks are raised under farm conditions where they scavenge for much of their feed. Throughout Southeast Asia, ducks have been integrated with aquaculture.

Ducks can be raised on almost any kitchen wastes: vegetable trimmings, table scraps, garden leftovers, canning refuse, stale produce, and stale (but not moldy) baked goods. However, for top yields and quickest growth, protein-rich feeds are the key. Commercial duck farms rely on such things as fish scraps, grains, soybean meal, or coconut cake. Agricultural wastes such as sago chips, palm-kernel cake, and palm-oil sludge are being used in Malaysia.4

Ducks have a very high requirement for niacin (a B vitamin). If chicken rations are used, a plentiful supply of fresh greens must be provided to avoid "cowboy legs," a symptom of niacin deficiency.

ADVANTAGES

Of all domestic animals, ducks are among the most versatile and useful and have multiple advantages, including:

- Withstanding poor conditions;

- Producing food efficiently;

- Utilizing foodstuffs that normally go unharvested;

- Helping to control pests; and

- Helping to fertilize the soil.

Also, they are readily herded (for instance, by children).

Excellent foragers, they usually can find all their own food, getting by on only a minimum of supplements, if any. Raising them requires little work, and they provide farmers with food or an income from the sale of eggs, meat, and down.

Ducks can grow faster than broiler chickens if they have adequate nutrients. Like guinea fowl and geese, they are relatively resistant to disease. They also have a good tolerance to cold and, in most climates, don't need artificial heat.

DOMESTICATING NEW DUCKS

Many species of ducks adapt readily to captivity; it is surprising, therefore, that only the mallard and the muscovy have been domesticated so far. Several wild tropical species seem especially worth exploring for possible future use in Third World farms, Because of the year-round tropical warmth, their instinct to migrate is either absent or unpronounced, and the heavy layer of fat (a feature of temperate-climate ducks that consumers in many countries consider a drawback) is lacking. Moreover, because of uniform daylength, they are ready to breed at any time of the year. Candidates for domestication as tropical ducks include:

- Whistling ducks (Dendrocygna species). These large, colorful, gooselike birds are noted for their beautiful, cheerful whistle.* They are long-necked perching ducks that are found throughout the tropics. By and large, they are gregarious, sedentary, vegetarian, and less arboreal than the muscovy - all positive traits for a poultry species.

The black-bellied whistling duck (D. auturunalis) seems especially promising. It is common throughout tropical America (southwestern United States to northwestern Argentina) and is sometimes kept in semicaptivity. Occasionally, in the highlands of Guatemala, for instance, Indians sell young ones they have reared as pets. When hand reared, the birds can become very tame. * * They eat grain and other vegetation, require no swimming water, and will voluntarily use nest boxes. In the wild, they "dump" large numbers of eggs so that even if substantial numbers were removed for artificial hatching, the wild populations should not be affected.

- Greater wood ducks (Cairina species). The muscovy (C. moschata) was domesticated by South American Indians long before Europeans arrived (see page 124). Its counterparts in the forests of Southeast Asia and tropical Africa are, however, untried as domesticates. The white-winged wood duck (C. scutulata) is found from eastern India to Java. Hartlaub's duck (C. hartlaubi) occurs in forests and wooded savannas from Sierra Leone to Zaire. Both are rare in captivity, but might well prove to be future tropical resources. Both are strikingly similar to muscovies in size and habits, being large, phlegmatic, sedentary, and omnivorous.

LIMITATIONS

Predators are the most important cause of losses in farm flocks. Ducks are almost incapable of defending themselves, and losses from dogs and poachers can be high. Locking them in at night both protects the birds and prevents eggs from being wastefully laid outside.

Ducks do suffer from some diseases, mainly those traceable to mismanagement such as poor diet, stagnant drinking water, moldy feed or bedding, or overcrowded and filthy conditions. Of all poultry, they are the most sensitive to aflatoxin, which usually comes from eating moldy feed. They are also susceptible to cholera (pasteurellosis) and botulism, either of which may wipe out entire flocks. Duck virus enteritis (duck plague) and duck virus hepatitis also can cause severe losses.

If not carefully managed, ducks can become pests to some crops, especially cereals.

As noted, ducks tend to be extremely poor mothers and can be helped by using broody chicken hens or female muscovies as surrogate mothers.

Major limitations to large-scale, intensive production are mud, smell, and noise.

Defeathering ducks is much more difficult than defeathering chickens because of an abundance of small pinfeathers and down feathers.

RESEARCH AND CONSERVATION NEEDS

These birds already function so well that no fundamental research needs to be done. Nonetheless, there are a number of topics that could improve their production.

For example, different types of low-cost systems need to be explored and developed. These must be low-input systems since cash is a limiting factor for most subsistence farmers. One possibility is the integration of duck and fish farming.

A survey of all breeds is needed to determine their status and likelihood of extinction.

One need in countries that already have ducks is to encourage the consumption of duck meat. Indonesia, for instance, has 25 million egg-producing ducks, but little duck meat is consumed.

Research on economically significant diseases is needed.