| Microlivestock - Little-Known Small Animals with a Promising Economic Future (b17mie) հղում աղբյուրինb17mie.htm |

| Part II : Poultry |

|

|

5 Chicken

FIGURE

Chickens (Gallus gallus or Gallus domesticus)1 are the world's major source of eggs and are a meat source that supports a food industry in virtually every country. There may be as many as 6.5 billion chickens, the equivalent of 1.4 birds for every person on earth.2

No other domesticated animal has enjoyed such universal acceptance, and these birds are the prime example of the importance of microlivestock. Kept throughout the Third World, they are one of the least expensive and most efficient producers of animal protein.

To the world's poor, chickens are probably the most nutritionally important livestock species. For instance, in Mauritius and Nigeria more than 70 percent of rural households keep scavenger chickens. In Swaziland, more than 95 percent of rural households own chickens, most of them scavengers. In Thailand, where commercial poultry production is highly developed, 80-90 percent of rural households still keep chickens in backyards and under houses. And in other developing countries from Pakistan to Peru, a similar situation prevails.

Clearly, these chickens should be given far more attention. They represent an animal and a production system with remarkable qualities; they compete little with humans for food; they produce meat at low cost; and they provide a critical nutritional resource.

Scavenger chickens are usually self-reliant, hardy birds capable of withstanding the abuses of harsh climate, minimal management, and inadequate nutrition. They live largely on weed seeds, insects, and feeds that would otherwise go to waste.

Unfortunately, however, quantitative information about the backyard chicken is hard to obtain. Few countries have any knowledge of its actual contribution to the well-being and diet of their people. Notably lacking is an understanding of the factors limiting egg production, which is markedly low and perhaps could be raised dramatically with modest effort.

AREA OF POTENTIAL USE

Worldwide.

APPEARANCE AND SIZE

Chickens are so well known and ubiquitous that they need no further description. Varying in color from white through many shades of brown to black, they range in size from small bantams of less than 1 kg to giant breeds weighing 5 kg or more. Scavenger chickens tend to weigh about I kg.

The indigenous chickens of Asia are probably descended directly from the wild junglefowl. Those of West Africa are believed descended from European birds brought by the Portuguese in the sixteenth century; those of Latin America probably descend from Spanish birds introduced soon after the time of Columbus.

figure

DISTRIBUTION

All countries have chickens in large numbers.

STATUS

They are not endangered, but industrial stocks are replacing traditional breeds to such an extent that much potentially valuable genetic heritage is disappearing.

HABITAT AND ENVIRONMENT

Although chickens derive from tropical species, they adapt to a wide variety of environments. The modern Leghorn, for example, is found from the hot plains of India to the frozen tundra of Siberia, and from sea level to altitudes above 4,000 m in the Andes. (There are, however, hatching problems at such high altitudes because of oxygen deficiency.) They also occur in desert countries such as Saudi Arabia, which has a vast poultry industry and even exports broilers. (However, the birds need shade and a lot of water where it is hot and dry.)

BIOLOGY

Chickens are omnivorous, living on seeds, insects, worms, leaves, green grass, and kitchen scraps.

A commercial bird may produce 280 eggs annually, but a scavenger may produce close to none. Commonly, a farmyard hen lays a dozen eggs, takes three weeks to hatch out a brood of chicks, stays with the chicks six weeks or more, and only then starts laying again.

Egg production depends on daylength. For the highest production rate, at least 12 hours of daylight are needed. The incubation period is 21 days. A hen can begin laying at 5 months of age or even earlier, but in scavengers it may be much later. The average weight of the eggs is approximately 55 g from industrial layers and approximately 40 g from scavengers. Hatching success from breeder flocks often exceeds 90 percent. Industrial broilers can be marketed as early as 6 weeks, when they are called "Cornish hens."

BEHAVIOR

These passive, gregarious birds have a pronounced social (pecking) order. If acclimated, they remain on the premises and are unlikely to go feral. If given a little evening meal of "scratch," they learn to come home to roost at night.

USES

Chickens have multiple uses. They were probably first used for cock fighting; later they were used in religious rituals, and only much later were raised for eggs and meat. Today, chickens can provide a family with eggs, meat, feathers, and sometimes cash.

HUSBANDRY

In different parts of the world, people keep scavenging chickens in different ways. The managers are often women and children because they have more time to spend at home to feed the birds and repel predators. Some people leave the birds entirely to their own devices. Many house them at night. Others take the birds each day to the fields, where they may find much more food.

There are many ingenious local practices. In Ghana, for example, farmers "culture" termites for poultry by placing a moist piece of cow dung (under a tin) over a known termite nest. The termites burrow into the dung, and some can then be fed to the chickens each day. Because termites digest cellulose, this system converts waste vegetation into meat.

A ratio of 1 male to 10-15 females is adequate for barnyard flocks. Hens will lay eggs in the absence of a rooster - but of course the rooster is needed if fertile eggs are wanted.

Removing chicks stimulates the hen to lay more eggs. This results in more chicks being hatched, but it requires that the chicks be nurtured and fed until they are old enough to fend for themselves.

ADVANTAGES

Chickens are everywhere; every culture knows them and how to husband them. They have been utilized for so many centuries that in most societies their use is ingrained. Unlike the case with pork and beef, there are few strictures against eating chicken meat or eggs.

The meat is high in quality protein, low in fat, and easily prepared. In many countries, the village chicken's meat is preferred to that of commercial broilers because it has better texture and stronger flavor. Even in countries with vast poultry industries there is a growing demand for the tasty, "organically grown," free-ranging chicken.

Chickens are more suited to "urban farming" than most types of livestock and can be raised in many city situations.

The birds are conveniently sized, easily transported alive, and, by and large, do not transmit diseases to humans.

LIMITATIONS

Throughout Asia, Africa, and Latin America, the problems of village chickens are mainly those discussed below.

High Hatching Mortality

Commonly, a hatch of eight or nine village chicks results in only two or three live birds after a few days. A survey in Nigeria, for instance, showed that 80 percent died before the age of eight weeks. Losses elsewhere are known to be similar. This is mostly because of starvation, cold, dehydration, predators (hawks, kites, snakes, dogs, and cats, for example), diseases, parasites, accidents, and simply getting lost - all of which can be prevented without great effort.

Chronic and Acute Disease

Poultry diseases can become epidemic in the villages because there are few if any veterinarians. Newcastle disease, fowlpox, pullorum disease, and coccidiosis, for example - all of which are endemic in the Third World - can destroy the entire chicken population over large areas. Lice and other parasites are also prevalent. Scavengers and industrial birds seem to show no differences in their tolerance for such diseases and parasites.

Low Egg Production

A survey in Nigeria showed that the annual production per hen was merely 20 eggs. Such low production is common throughout the Third World and is caused by a combination of low genetic potential, inadequate nutrition, and poor management. Villagers rarely provide nest boxes or laying areas, so that some eggs are just not found. Some birds have high levels of broodiness, and eggs accumulating in a nest stimulates this. There are indications, however, that some village chickens (for example, some in China) have quite substantial egg-laying potential when provided with adequate feed.3

Low Egg Consumption

In the tropics, many people choose not to eat eggs. Often this is because eggs are the source of the next generation of chickens; sometimes it is because of superstition. Further, eggs do not keep well because most are fertile and, exposed to constant tropical heat, undergo rapid embryo development.

Crop Damage

It is often necessary to confine the birds to protect young crops or vegetable gardens.

RESEARCH AND CONSERVATION NEEDS

Unlike the situation with small cattle, goats, sheep, and pigs, there are few named and recognized breeds of Third World chickens. Yet, nearly every country has at least one kind of village chicken. These have survived there for centuries and are highly adapted to local conditions. In village projects, these unnamed chickens deserve priority attention before other types are sought from elsewhere.

Generally speaking, improving the production of scavenging poultry does not require sophisticated research. Instead, simple precautions are sufficient. These are discussed below.

Disease Control

At a national or regional level, the initial approach to increasing chicken production in tropical areas should be disease control. There are several outstanding instances of success in this endeavor. For example, the spectacular rise of poultry production in Singapore (from 250,000 birds in 1949 to 20 million in 1957) followed the control of Ranikhet disease. Village flock-health programs, carried out regularly by visiting veterinarians ("barefoot veterinarians"), might be the answer to some of the routine health problems. Today, a prime target should be Newcastle disease, for which there are good chances for success (see page 76).

Management

The first step in chicken production at the farm level is improved management. With more care and attention, mortality can be greatly reduced. Because incubating and brooding hens must spend the night on the ground, they are extremely vulnerable. Even modest predator controls can be highly beneficial. Building crude and inexpensive nest boxes and constructing a simple holding area around them can substantially raise production by ensuring that more chicks survive.

THE CHICKEN'S WILD ANCESTOR

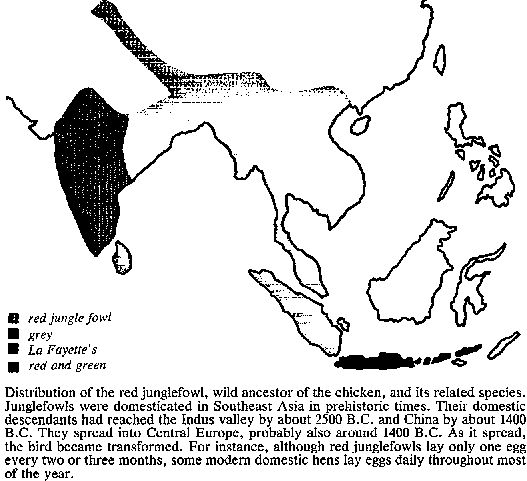

Although little known to most people, the red junglefowl has contributed more to every nation than any other wild bird. It is the ancestor of the chicken.

Given its descendants importance worldwide, the neglect of this bird is baffling. If the cow's wild ancestor, the aurochs, had not become extinct in the 1600s, it would now be worth millions of dollars as the ultimate source of cattle genetic diversity. Yet the world's chicken industry remains virtually unaware of the origin of its source of livelihood.

Like the aurochs, the red junglefowl has a wealth of wild genes, and it deserves more recognition and protection. For one thing the modern chicken - selectively bred in the temperate zone - is highly susceptible to heat and humidity; the junglefowl, on the other hand, is not. It inhabits the warmest and most humid parts of Asia: Sri Lanka, India, Burma, Thailand, and most of Southeast Asia. It may also be resistant to various chicken diseases and pests.

This is not a rare species. Throughout the wide crescent stretching from Pakistan to Indonesia, junglefowls are still seen in the wild, especially in forest clearings and lowland scrub. Although they are a prized bag for hunters, they survive by fast running and agile flying. They are sometimes sold in village markets, but can easily be mistaken for domesticated chickens, which in this region are often very similar. The wild junglefowl, however, has feathered legs, a down-curving tail, and an overall scragginess.

Junglefowls should be under intensive study. They are easy to rear in captivity and do well in pens, even small ones, as long as they are sheltered from rain and wind. One drawback is their craze for scratching unless provided plenty of space they promptly tear up all grass and dirt. Another is that junglecocks are violent fighters and must be kept apart. (Cockfighting is probably a major reason why they were initially selected, and thus their aggressiveness is perhaps the reason we have the chicken today.)

These highly adaptable creatures live in a variety of habitats, from sea level to 2,000 m. Most, however, are found in and around damp forests, secondary growth, dry scrub, bamboo groves, and small woods near farms and villages. They are amazingly clever at evading capture and thrive wherever there is some cover.

Other junglefowl species might also provide useful poultry. They, too, can be raised in captivity with comparative ease, as long as the cocks are kept apart. Perhaps they might be tamed with imprinting and could prove useful as domestic fowl, especially in marginal habitats. They are everywhere considered culinary luxuries and their meat commands premium prices. Moreover, several have colorful feathers, giving them additional commercial value. These other species are:

- La Fayette's Junglefowl (Gallus lafayettei). Avery attractive bird of Sri Lanka, it is little known in captivity, and only in the United States are there any number in captivity.

- Gray or Sonnerat's Junglefowl (Gallus sonnerati). A native of India, this colorful bird produces feathers that are used in tying the most prized trout and salmon flies. Demand is so great that certain populations have declined, and since 1968 India has banned all export of birds or feathers. Nonetheless, there are several hundred in captivity in various countries.

- Green Junglefowl (Gallus varius). This is yet another striking bird. The cock has metallic, greenish-black feathering set off by a comb that merges from brilliant green at the base to bright purple and red at the top. Native to Java, Bali, and the neighboring Indonesian islands as far out as Timor, it is found particularly near rice paddies and rocky coasts. This species, too, can be raised without great difficulty, and there are at least 90 in captivity in various parts of the world.

Nutrition

Improving poultry nutrition is also of prime importance. There are no quantitative data on the quality of a scavenging chicken's diet. Surveys are badly needed so that appropriate, low-cost supplements can be devised.

Chances are that the diet for chicks of scavenging poultry is almost always deficient in available energy. Minimal supplementation in the form of cereals or energy-rich by-products can greatly improve both egg and meat production. However, caution must always be exercised and the supplements given only to chicks. Overfed adults will give up scavenging and stay around the owner's house, without really producing much more meat or eggs.

Genetic Improvement

Although it seems attractive to replace the scrawny village chicken with bigger, faster-growing imported breeds, it is a process fraught with difficulty. Exotic breeds lack the ability to tolerate the rigors of mismanagement and environmental stress. Many cannot avoid predators, as a result either of being overweight or of having a poor conformation for flight. The local birds, however, probably have a genetic potential that is much higher than can be expressed in the constraining environment. Thus, the environmental constraints should be tackled first.

However, the village birds may have a feed-conversion efficiency that is far less than ideal because they are adapted to a scavenging existence. Modern breeds imported into Ghana, for instance, showed a feed-conversion efficiency of less that 3.5:1 (weight of food eaten: growth and eggs), but the local birds had efficiencies of 11:1.4

Conservation

The need for preserving genetic variability is greater in poultry, especially in chickens, than in any other form of domestic animal. North America, for instance, which years ago had 50 or more common breeds, now relies on only 2 for meat production, and the others have been largely lost. Conservation of germplasm has become a matter of serious concern, and the saving of rare breeds in domestic fowl should not be delayed.

THE SOUTH AMERICAN CHICKEN

Early European explorers of South America were surprised to discover an abundance of unusual chickens that laid colored eggs and had feathers resembling earrings on the side of the head. While the origin of this bird - commonly called the araucanian chicken and classified as Gallus inauris - is debatable, scientists generally agree that it is pre-Columbian. There is archeological evidence that this bird is native to the Americas. It is reported to have occurred in Chile, Ecuador, Bolivia, Costa Rica, Peru, and Easter Island. It still occurs in the wild in southern Chile and on Easter Island.

The araucanian has been called the "Easter-egg chicken" because it lays light green, light blue, and olive colored eggs. It lays well and has a delicious meat. In areas such as southern Chile the eggs are preferred over those of normal chickens because of their flavor and dark yellow yolk. This unusual bird has a high degree of variability; however, specimens of similar genetic background have been grouped to create "breeds" such as the White Araucanian, Black Araucanian, and Barred Araucanian. These are homozygotes and breed true.

The araucanian has been the subject of much public interest,. clubs dedicated to its preservation have been formed in the United States, Great Britain, and Chile. Its possible exploitation as a backyard microlivestock deserves serious consideration.