| Microlivestock - Little-Known Small Animals with a Promising Economic Future (b17mie) հղում աղբյուրինb17mie.htm |

| Part I : Microbreeds |

|

|

4 Micropigs

FIGURE

Most breeds of swine (Sus scrofa) are too large to be considered microlivestock, but there are some whose mature weight is less than 70 kg. These micropigs are particularly common in West Africa, South Asia, the East Indies, Latin America, and oceanic islands around the world. At least one, the Mexican Cuino, may weigh a mere 12 kg full-grown.

Many miniature swine have been developed for use in medical research, but their agricultural potential has been largely ignored. This is unfortunate, for micropigs of all types - native, feral, and laboratory - deserve investigation. Swine provide more meat worldwide than any other animal, and micropigs are potentially important sources of food and income for poor people in many parts of the developing world.

Smallness makes for nimble and self-sufficient pigs, in contrast to large, lethargic breeds. Small breeds are easier to manage and cheaper to maintain; the threat of injury from angry or frightened animals is lessened; and the sows are less likely to crush newborn piglets, often a major cause of mortality in large breeds. Some micropigs - particularly those from hot regions or wild populations - also have a higher resistance to heat, thirst, starvation, and some diseases.

Pigs adapt to a wide variety of management conditions, from scavenging to total confinement; some are even kept indoors.2 They gain weight quickly, mature rapidly, and help complement grazing livestock because they relish many otherwise unused wastes from kitchens, farms, and food industries, as well as other foods such as small roots, leafy trash, or bitter fruits that are not consumed by humans or ruminants.

For these reasons, micropigs could become useful household and village livestock in the developing world, and they deserve greater attention than they now receive. Although their growth may not be as rapid as that of improved breeds raised under intensive commercial production, with modest care and minimum investment, backyard micropigs can produce sizable yields of meat and other products, as well as improved income for rural and even urban populations.

AREA OF POTENTIAL USE

Worldwide, especially in warm, humid areas.

APPEARANCE AND SIZE

Like full-sized breeds, micropigs are stout-bodied, short-legged animals with small tails and flexible snouts ending in flat discs. Examples of some micropigs are listed at the end of the chapter.

DISTRIBUTION

Domestic pigs are found all over the world, but their concentrations vary greatly. Africa has the fewest per capita, but in recent years they have gained increasing favor in the sub-Saharan regions. In Latin America, pigs have long been a major component of backyard agriculture. In the Middle East, an early center of domestication, pigs are not widely kept today because of religious dietary restrictions. In the Ear East, they are the major meat source, and China has more pigs than any other country. And in the Pacific region, pigs and chickens are often the only meat available.

STATUS

Pigs are becoming more popular: their worldwide numbers increased by about 20 percent in the 1970s. However, in most countries commercial pig production has focused on a mere handful of breeds, and much genetic diversity is unstudied or even threatened with extinction. Some microbreeds have already been lost, and others are dwindling in numbers.3 Many European breeds have been completely lost. The Cuino and some other Latin American criollo types are threatened, as are most of Africa's traditional breeds. China, however, has made notable efforts to preserve its native types.

HABITAT AND ENVIRONMENT

Although, as previously noted, pigs are found all over the world, they are in general adapted to warm, humid climates where many other livestock species are more susceptible to diseases and environmental stresses. They are also raised at high altitudes, such as in the Andes and Tibet. Although there are few climatic limitations to pig production, only about 20 percent of the world's pigs are currently kept in the tropics.

BIOLOGY

Pigs are omnivores, willing and able to eat almost anything.4 Unlike most other livestock, they eat their fill and sleep as the food digests, allowing humans to establish a convenient eating and sleeping schedule.

Pigs are prolific; a few Chinese breeds routinely have litters of 20 or more. Micropigs are no exception; litters of 6-10 are common. Piglets gain weight rapidly and can be weaned after a few weeks. Sexual maturity is sometimes attained as early as 4-6 months, depending on breed and environment. Pigs are usually slaughtered at 67 months of age, allowing them to be produced on an annual cycle. They can live 10-20 years.

Because of their smaller size, micropigs have a relatively greater skin-to-weight ratio than today's commercial breeds, and therefore they probably shed heat more effectively. Certainly they seem to perform better in tropical heat and humidity, which normally keep the heavier types from reaching their maximum productivity. Studies have suggested that an optimal size for some tropical environments - because of metabolic and feed efficiency - may be less than 65 kg.5

BEHAVIOR

Pigs are social animals; they enjoy companionship and ferociously defend their young and sometimes even the humans who care for them. They are employed as guard animals in some areas and have been used extensively in behavioral research.

Contrary to common belief, pigs are clean and tidy if provided adequate space. Larger breeds, however, wallow in mud to stay cool in hot weather and require a wallow or shade (except for some Latin American types, which seem less susceptible to heat). Some lightcolored pigs sunburn easily.

Pigs will dig up earth with their mobile snouts; some breeds do it constantly.

USES

Fresh pork is the major pig product in tropical areas. It usually fetches premium prices, and in many places (such as the Pacific Islands and China) it is the most important red meat available to rural people. Nutritious and tasty, it is one of the easiest meats to preserve, needing only salt or melted fat. Processed products such as bacon and sausages can be important for both home consumption and cash sales.

Pig fat (lard) is a good source of food energy, and can substitute for cooking fats and oils. It is easily melted and clarified, is widely used to make soap, and is a valuable commercial product.

Pig skin, once degreased, is easily tanned into leathers that are popular for garments, shoes, and other products demanding soft, light, and flexible leathers.

Pig manure is a good fertilizer. Because the animals are often kept in confinement, it can be easily collected.

HUSBANDRY

In many places, pigs are kept as free-roaming scavengers. They can be trained (by coaxing with feed, salt, or affection) to keep close to home, thereby helping to minimize destructive scavenging.

Herding is a higher level of management that requires more effort, but it allows pigs to be integrated into other types of agriculture while utilizing feeds that otherwise go to waste.

Because their exercise needs are minimal and dominance is quickly established within litters, pigs are the easiest hoofed livestock to raise in small enclosures (sties). However, fencing must be secure, and if sties are small, the animals must be moved frequently to prevent diseases and parasites from building up.

ADVANTAGES

Pigs are well-known, often traditional, animals in many areas, and people usually do not have to be taught how to manage and use them. Efficient scavengers, they can live, grow, and reproduce with a minimum of investment or specialized care.

Pigs are highly efficient converters of feed to meat. They can provide the greatest return for the least investment of any hoofed livestock because of their fecundity, low management costs, broad food preferences, and rapid growth.

Pigs normally accumulate fat during adolescent growth (making ''finishing" feeds less necessary). Some micropigs (especially those from feral ancestors) have the ability to quickly mobilize and store these body-fat reserves; in times of extreme scarcity, it aids their survival.6

Pigs work well in multiple-cropping schemes. They are often used to help clear small plots by uprooting weeds, shrubs, and even small trees. In Southeast Asia, they are frequently raised in conjunction with aquaculture, their manure providing food for the fish.

LIMITATIONS

If improperly managed or maintained in filthy conditions, pigs may quickly succumb to disease and parasite epidemics. Most diseases are communicated only among pigs, but some can be transmitted to humans. For this reason, pork should always be fully cooked.

Some cultures never eat pork. Others do, but nonetheless accord pigs and their keepers low status.

Young pigs are vulnerable to many predators.

RESEARCH AND CONSERVATION NEEDS

A major survey of small pig breeds is needed. They have the potential to be valuable producers in their own right, as well as to improve other pig breeds. For instance, they represent a little-known reservoir of disease resistance and climatic adaptation. Governments, research stations, universities, and individuals should make special efforts to preserve types that have outstanding or unusual qualities.

When it is necessary to eradicate feral pig populations (as is common on Pacific islands), representative stocks should be preserved. These rugged animals have been genetically isolated for decades or even centuries and are likely to carry valuable traits for survival under adversity.

Large breeds may be promising candidates for genetic "downsizing," which has already produced the many types of miniature pigs that are used in medical research.

THE LITTLEST PIG

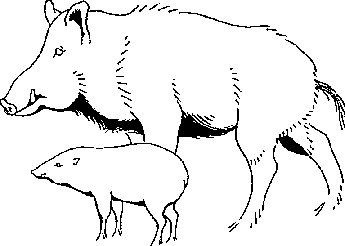

Although this chapter highlights the world's smallest breeds, there exists a pig that is even smaller. It is, however, an entirely different species and it is on the brink of extinction.

The pigmy hog (Sus salvanius) is a shy and retiring wild creature of northeastern India. It is merely 60 cm long with a shoulder height of 25 cm, and weighs less than 10 kg. It was once found widely along the southern foothills of the Himalayas. Today, however, it apparently occurs in only one area, the Manas National Park in Assam. Despite this protection and the fact that it is listed among the 12 most endangered species on earth, it still falls victim to hunters and to habitat destruction - especially illegal grass fires.

If saved from extinction, this minute species - barely reaching a person's calf - might become useful throughout the world. Its chromosome number is the same as that of the common pig and its physiological processes are probably also similar. Therefore, were its numbers to be built up, it might become a valued and well-known resource for laboratories and small farms. Its daily food intake and its space requirements are only a fraction of a normal pig's. It probably has exceptional tolerance to heat, humidity, and disease.

This is not a domesticated species, and there is therefore much to learn before its usefulness can be clearly seen. Indeed, whether it can be reared in captivity is uncertain. Some attempts have ended in disaster, but this seems to have been the result of mismanagement.

Before there is any possibility of developing it, however, the pigmy hog must be preserved from ultimate loss. The last specimen could go into a villager's pot at any time now.

Adult male of the common pig (wild boar) and pigmy hog draw to same scale. (W.L.R. OLIVER)

REPRESENTATIVE EXAMPLES OF MICROPIGS

West African Dwarf (Nigerian Black, Ashanti)

West Africa. Mature weights of 25-45 kg are reported. In the humid lowland forests of West Africa this breed has long been kept by villagers, often as a scavenger. Indigenous to the hot, humid tsetse zones of West Africa, it seems resistant to trypanosomiasis.

Chinese Dwarfs

China (and Southeast Asian countries such as Vietnam) has long had small pigs - often characterized by numerous teats and large litters - associated with traditional intensive agriculture as well as scavenging conditions. Some Chinese pigs weighing less than 70 kg are adapted to tropical and subtropical conditions, but the smallest (20-35 kg) live in the cold climates and high altitudes of Gansu, Sichuan, and Tibet. Small black Chinese pigs were crossed with European types in the early 1800s and produced the foundation stock of many modern Western breeds.

Criollo

There are a number of "native" breeds throughout Latin America commonly known as "criollo." Many are quite small. Although, apparently, they are slow to mature and bear small litters, they adapt well to environmental extremes and are widely kept by rural inhabitants for food and income. Criollos are little studied and are being replaced by imported breeds before their possibly outstanding qualities can be quantified.

Cuino This micropig from the highlands of central Mexico may be descended from small Chinese types and is the smallest domestic pig, weighing as little as 10-12 kg fully grown. Hardy and an efficient scavenger, it can grow quickly when feed - especially corn - is abundant. A century ago the cuing was a widespread household animal and was used for a time for experimental work in central Mexico. It is now little known and could be threatened with extinction.

Black Hairless (felon, Tubasqueno, Birish) These small pigs of central and northern South America survive in hot, humid, adverse climates. They are adapted to bulkier feeds than most pigs and can thrive on fruit wastes. Many local types exist.

Nilo (Macao, Tatu, Canastrinha) This small, widespread, black, hairless pig of Brazil is often kept inside the house.

Yucatan Miniature Swine A subtype of the black hairless from Mexico's hot, arid Yucatan Peninsula, it was imported into the United States in 1960. It has been downsized for laboratory use in the United States and is known as the Yucatan Micropig (registered). Weight at sexual maturity has been lowered through selective breeding from 75 kg to, currently, between 30 and 50 kg, with an ultimate goal of 20-25 kg. There is no evidence of "dwarfism," stunting, or loss of reproductive performance, and it appears to hold notable promise as microlivestock for developing countries. The parent stock, used for meat and lard production in Yucatan, is renowned for gentleness, intelligence, resistance to disease, and relative lack of odor. Exceptional docility, even in older boars and sows with litters, makes them easy to handle without the need for specialized housing or equipment.7

Other Laboratory Breeds

Other miniature laboratory pigs have potential for tropical use. These include the Goettingen, Hanford, Kangaroo Island, Ohmini, Pitman-Moore, and Sinclair (Hormel). In general they weigh 30-50 kg when ready for slaughter and mature at less than 70 kg.

Ossabaw

United States. 20-30 kg. Feral on Ossabaw Island, South Carolina, for more than 300 years, this pig is well adapted to environmental extremes. Unlike most domestic animals, it can maintain itself in coastal salt marshes. It has perhaps the highest percentage of fat of any pig. The piglets are very precocious, self-reliant, and robust.8

Kunekune (Pua'a, Poaka)

New Zealand. Female 40 kg; male 50 kg. Perhaps of Chinese origin, these black-and-white spotted pigs are docile, slow, and easy to contain. Although late maturing, they can fatten on grass alone. Like other native breeds throughout the Pacific region (for example, the Pauta of Hawaii), stock is being lost through crossbreeding, displacement by other breeds, and eradication efforts.

To find certain disease-resistant genes in poultry it may be necessary to go looking in the backyard chicken flocks in Latin America, Africa, or Asia.

Kelly Klober

Small Farmer's Journal

. . . Policies are needed to encourage development of a labor-intensive small-scale livestock sector, which would increase employment and provide a major market for surplus cereals. This sector, however, is particularly restrained by poor technology, poor public support services, and poor marketing channels. Third World livestock production of this type could provide a natural focus for foreign assistance that earlier seemed inappropriate because of concerns about global food scarcity.

John W. Mellor International Food Policy Research Institute

Successful development of agriculture often requires an intimate understanding of the society within which it is to take place - of its systems of values, of its customary restraints.... It has been necessary to understand what incentives the farmer needs to change, what practical difficulties he encounters introducing change, what his traditional pattern of land use is and how this pattern or system can be upset by thoughtless innovation.

John de Wilde

Experience with Agricultural Development in Tropical Africa