| Development in practice: Toward Gender Equality (wb34te) source ref: wb34te.htm |

| Chapter two |

Chapter two

Gender Inequalities Hamper Growth

Inequality women and men limits productivity ultimately slows economic growth. early empirical studies (for example, Kuznets 1955) suggested that income inequality would increase with economic growth during the initial phases of development. This chapter, however. starts with the hypothesis that there is not necessarily a tradeoff between inequality and growth and. indeed that high inequality especially as it affects human capital. hampers growth (Fields 1992: Birdsall and Sabot 1994).

Both theory and empirical evidence point to the importance of human capital in creating the necessary conditions for productivity growth and in reducing aggregate inequality in the future. In addition. women s human capital generates benefits for society in the form of lower child mortality. higher educational attainment improved nutrition. and reduced population growth. Inequalities in the accumulation and use of human capital at-e related to lower economic and social well-being for all.

Household and Intrahousehold Resource Allocation

In recent years, attempts to explain persistent gender inequalities in the accumulation and use of human capital have focused on the key role of household decisionmaking and tile process of resource allocation within household Households do not make decisions in isolation. however: their decision are linked to market prices and incentives and are influenced by cultural legal and state institutions. These institutions indirectly affect not only the returns on household investment but also access to productive resources and employment outside the house hold.

Household decisions about the allocation of resources have a profound effect on the schooling, health care, and nutrition children receive. The mechanisms used to make these decisions and the effect of the decisions on the well-being of individual household members are not fully understood. Two frameworks for thinking about household decisions are the unitary household model and the collective household model (see box 3.1)

|

BOX 2.1 Two models of household members having their own prefer decisionmaking encase. Decisions on allocating resources reflect market rates of return. The unitary household model assumes but they also mirror the relative bar that household members pool regaining power of household members sources and allocate them according within the collective (Manser and to a common set of objectives and Brown 1980: McElroy and Homey goals. Households maximize the joint 1981). Bargaining power is a function welfare of their members by allocating of social and cultural norms. as well income and other resources to the in as of such external factors as opposed individuals and enterprises that promise "unities for paid work, laws governing the highest rate of return as reflected inheritance, and control over producing prices and wages. An increase initiative assets and property rights. These household income increases the well factors influence the terms governing being of all household members. |

Policy interventions based on the sources and decisions about how unitary household model aim to in those resources are used within the crease household welfare, but they household. Thus, an increase in do not necessarily affect all household income may benefit some hold members in the same way. Some household members but leave others household members may be worse unaffected or worse off. The outcome off, for example, if they lose control depends on a member's ability to exover certain resources; others may excise control over resources both in be better off. in which case house-side and outside the household, and it hold welfare is not maximized. cannot be assumed that individual well

Under the collective household being increases as household income model. the welfare of individual house-rises. (Collective household models do hold members is not synonymous with not exclude the possibility that the universal household welfare. Resources unitary model may be the best approximate not necessarily pooled, and the motion of household decisionmaking household acts as a collective, with in some contexts.)

The collective household model helps explain why gender inequalities persist even though household becomes increase over time The next sections adopt a collective household framework to explain how these inequalities exact costs in forgone productivity, seduced welfare for individuals and households, encl. ultimately. slower economic growth.(fender Inequalities in Human Capital )

There are strong complementaires between education. health. and nutrition on the one hand, and increased well-being, labor productivity, and growth. On the other. Inequalities in resource allocation that limit household members' educational opportunities. access to health care, or nutrition are costly to individuals, households, and the economy as a whole.

Linkages between Education Health, and Nutritious

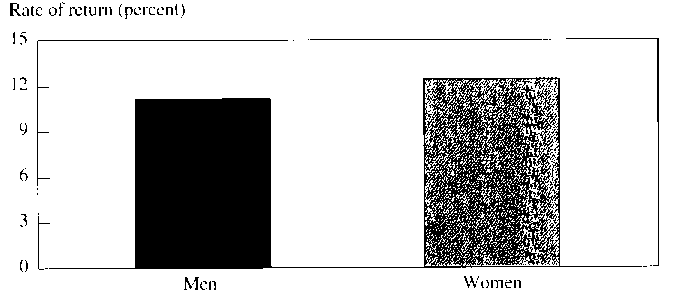

At the household level. gender differences in access to education are closely related to inequalities in the shares of household education expenditures allocated to boys and to girls This finding stands even though private returns to girls' schooling are similar to or marginally higher than. those to boys' schooling (figure 2.1; see also Schultz 1988: Mwabu 1994). In this case. parental choice reflects the relatively greater restrictions on educational opportunities and employment choices for girls. in comparison with boys. and cultural norms on the appropriate role for girls within the household.

Figure 2.1 private returns to education

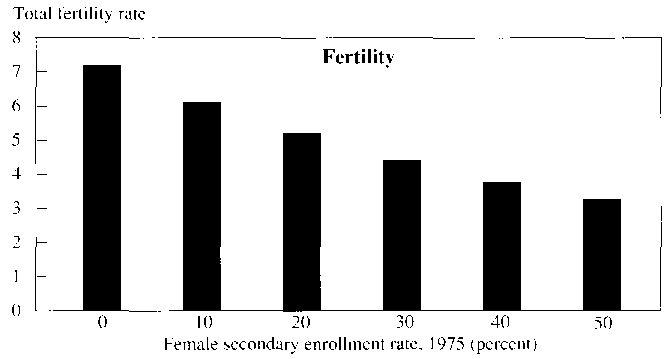

Figure 2.2 education, fertility. and child mortality (a)

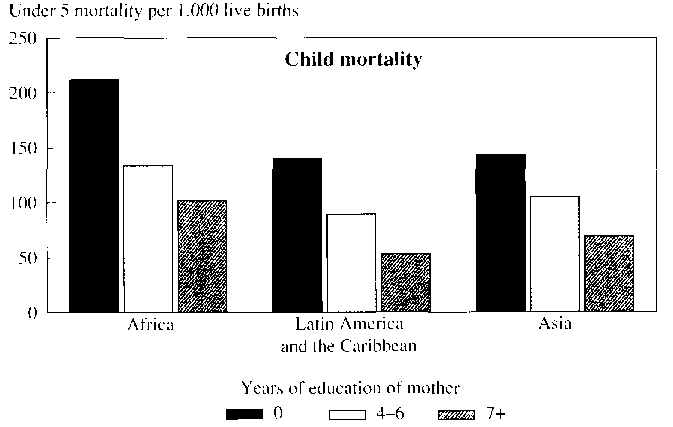

Figure 2.2 education, fertility. and child mortality (b)

More importantly. the social externalities linked to female education are crucial. Evidence from a large number of countries shows that female education is linked with better health for women and their children and with lower levels (figure 2.2). This link stems from the direct effect of education on the value of a woman's time and consequently. on private returns to her labor. It also stems from the indirect effect of education on the average age at which women marry on their knowledge of basic health care and nutrition, and on reproductive choices (Rosenzweig and Schultz 1982, 1987).

Educating girls and women reduces maternal mortality and fertility rates and increases the demand for health services. A simulation study of seventy two developing countries shows that, with all other factors held constant, a doubling of female secondary school enrollments in 1975 would have reduced tile average fertility rate in 1985 from 5.3 to 3.9 children per household and would have lowered the number of births by 29 percent (Subbarao and Raney 1992. Studies for individual countries have found that one additional year of female schooling can reduce the fertility rate. on average, between 5 and 1 (i) percent (Summers 1994)

Women are more vulnerable than men to micronutrient deficiencies that aggravate poor health (World Batik 1994b). Poor health and nutrition reduce productivity and the chances of reaping gains from investment in education. Intrahousehold inequalities in consumption and nutritional allocations can therefore be a signal of inefficiency Recent estimates suggest that the com effects on morbidity and mortality of just three types of deficiency-in vitamin A, iodine. and iron-could waste as much as 5 percent of gross domestic product (GDP), yet correcting these deficiencies would cost less than 0.3 percent of low-income countries' GDP (World Bank 1994c, pp. 50-51). Studies of women tea producers in Sri Lanka and of women workers in Chinese cotton mills document the reduction in productivity associated with iron deficiencies and the positive effects of in-on supplementation on work and output (Edgerton and others 1979). A study of six villages in Andhra Pradesh, India, found that disabling conditions caused by malnutrition and the prevalence of diseases reduced female labor force participation by 22 percent (Chatterjee 1991).

Physical anti mental abuse can also have deleterious effects on the well-being and productivity of women (table 2.1). Violence against women is widespread in all cultures and cuts across all age and income groups Its consequences. include unwanted pregnancy. infection with STDs, miscarriage partial or permanent disability. and psychological problems such as depression anti low self-esteem. Recent World Bank estimates indicate that in both industrial and developing countries domestic violence and rape cause women of reproductive age to lose a significant percentage of really days. Domestic violence appears to be an example of how the relatively weaker bargaining power of women and the paucity of options for them outside the home can affect the intrahousehold distribution of welfare.

Violence against Women Starts in the Womb and Continues trough Life

Table 2.1 Violence against women through the life cycle

|

Phase |

Type of violence |

|

Pre birth |

Battering during pregnancy (emotional and physical effects on the ottoman) effects on birth outcome |

|

Infancy |

Female infanticide: emotional and physical abuse |

|

Girl hood |

Sexual abuse by family members and strangers: forced child prostitution |

|

Adolescence |

Dating and courtship violence: economically coerced sex: sexual abuse in the workplace: rape: farce prostitution and trafficking in women |

|

Reproductive |

Coerced pregnancy: rape: abuse of women by male partners: down abuse and murder partner homicide psychological abuse sexual abuse of unmarried and childless women: abuse of women with disabilities |

Source: Heise 1993

Prospects for gainful employment. as well as the availability of basic social services such as water supply and sanitation. also influence women's well-being. The survival chances of female children in India appear to increase as the employment rate for women rises and the earnings differential between men and women decreases Battilan 1988 Dowry and marriage practices. along with household ownership of land are closely linked to women's chances of survival The effect of such practices cannot be over late. Sen's (1990) comparison of female-male mortality rates in China. India. and Sub-Saharan Africa suggest that more than 100 million women are "missing"

Public spending on social services affects the ability of individuals and households to benefit from their own private spending on human capital. In most industrial countries mortality rates decreased even before modern medical care became widely available, mainly because of improved water supplies and sanitation. The same is likely to hold for the developing world. Public interventions that address market under provision of water and sanitation facilities and shortages of health set-vices such as immunization and family planning-have a significant effect. and one that is probably greater for women than for men.

Lack of data makes it difficult to evaluate the effects of public spending on the educational attainment and health of women and men Very little empirical evidence in this area exists, but there is some indication that the proportion of public subsidies for education that benefits females is lower than the proportion that benefits males. In Kenya in 1992-93. for example. public spending on education amounted to the equivalent of an annual subsidy of 605 Kenyan shillings per capita: males received. on average. 670 shillings and females only 543 shillings. In Mexico the gender difference in public education subsidies was somewhat less: in Pakistan males received almost twice the female subsidy. Gender inequalities in the distribution of subsidies are greater at high than at primary levels. In Pakistan girls receive, on average. only 96 rupees a year for secondary school bag. compared with 58 rupees for boys. Box 2.2 explains how these figures are calculated.

Supply-side differences are partly a function of poorly targeted resources (as. for example, when more is spent on tertiary than on primary schooling). More importantly. they reflect differences in household demand for education for girls and boys. If more girls attended anti stayed in school. the proportion of public subsidy going to girls would he greater.

In health care assessing the incidence of public spending by gender is particularly difficult because of the marked differences in the health needs of women and men. These differences are related to different biological re

The main advantage of this type of analysis is that it measures how well public services are targeted to certain groups in the population, including women, the poor, and residents of regions of interest. Requirements anti to women's reproductive and childbearing roles. Some evidence suggests that because of these differences. per capita health cat-e subsidies to women are the same as and sometimes larger than those to men What is clearer is that women are less likely than men to seek health care. including in many countries. hospital care when it is netted and ate mote likely to consult a non medical health cat-e worker (lather than a qualified medical practitioner). Education tends to increase the likelihood that women will seek health care. whether public or ace the likelihood that women will seek health care. whether public or private (World Bank 1994b).

The importance of private and public investments in education and health services that will improve women's well-being is cleat. These services at-e also important for another season: these is important evidence that increases in women's well-being yield important intergenerational benefits and productivity gains in the future World Bank Living Standards Measure Study (LSMS) surveys car-tried out in Nicaragua (1993 Viet Nam 1993) Pakistan (1991), and Cote (1988) suggest that the probability of children being enrolled in school increases with their mother's educational level and that (controlling, for income and household size) girls. particularly those in non poor households. are mote likely to attend school if their mothers attended school. Other studies show that households with educated mothers lend to provide children with greater quantities of mote nutritious food often at a lower cost. than households with poorly educated mothers (Thomas 1990b)

Data from Brazil show that giving women more control over nonlabor income has a larger impact on child measures, nutritional intakes, and the proportion of the household budget devoted to human capital inputs than if men had control of this income (Thomas 1993) Other studies indicate that women spend proportionately mote of the income they control on health care for children than do men. Women also spend more on food products (as opposed to such goods as alcohol and tobacco) than men do (Duraiswamy 1992: Hoddinot and Haddad 1992) But fathers education is also important especially in interaction with mothers' education (Thomas 1990a)

Other studies have shown that children's educational attainment is lowest in households whet-e the male head has no schooling In Ghana the impact of a mother's education on her children's schooling is reduced when their father has no schooling. even after controlling for income and household size (Lavy 1992).

Material health (which is linked to education) also has important intergenerational effects. Children of mothers who are malnourished or sickly or receive inadequate prenatal and delivery cat-e face a greater risk of disease and premature death. Iodine-deficient mothers run a greater risk of giving birth to infants with severe mental retardation and other congenital abnormalities than do healthy mothers. Reduced fertility and improved health for women can increase individual productivity and improve family well-being. When good health is combined with education and access to jobs. the result is higher rates of economic growth.

Household and Labor Market Linkages

The link between the household and the labor market is particularly important. Specialization of labor within the household-whether individually chosen. socially determined. or legally induced-can accentuate gender inequalities in the formal and informal labor markets by leaving most of the unpaid work to women. This situation arises from convention rather than from comparative advantage Inadequate public and community services. transport. and housing also often have an uneven effect on the way men and women spend their time and can increase the demand for goods produced at home using unpaid labor (Moser 1994) Thus women may spend its much (or more time on unpaid work as on market work. In some countries this unpaid work contributes as much as one-third to the economy recorded GDP-and even mote to the welfare of poor families.

The amount of time women contribute to household production and maintenance, direct income generation. and family care combined is widely held to exceed that of men Analysis of data from Bangladesh. Botswana. Ghana. Kenya. Pakistan. the Philippines. and Zambia on how rural women spend their time confirms that, although use of time by women, and by different generations of women varies according to location. available technology. household characteristics. and cultural norms. gender bias in time use is widespread.

Women are generally responsible for collecting fuelwood and carrying water. Girls and alder women often do most of this work, although cultural norms in some countries affect women s mobility. The amount of time allocated to these activities is influenced by seasonal patterns of agricultural activity. the availability of substitute goods and services. and environmental changes. A study in Nepal, for instance, found that deforestation associated with a 75 percent rise in the time per trip would increase the time spent gathering fuelwood by 45 percent for all adults and by 50-60 percent for women.

In addition to fuel and water collection, child care is another activity that dominates women s time-although. considering the importance of children to future household welfare, the amount of direct time spent with children is limited. The seven-country study suggests that more time is spent on child cat-e in female-headed households. Female-headed households tend to have high dependency ratios and relatively large numbers of children, Implying more child-care time overall, but not necessarily on a per child basis. (Kumar and Hotchkiss 1988).

When a large proportion of women's use of time goes unrecorded the design of projects and policies can yield false evaluations of costs and benefits. For example, women's unpaid work may be assumed to have zero value. As a result, women's response to changing incentives may be predicted as being higher than their time constraints actually allow. Project benefits-such as the time saved by locating piped water close to homes or by expanding rural electrification-may also be undervalued. Conversely, the benefits of treeing up time may be far more significant than might have been thought. A study in Tanzania, for example. shows that relieving certain time constraints in a community of smallholder coffee and banana growers increases household cash incomes by 10 percent, labor productivity by 15 percent, and capital productivity by 44 percent (Tibaijuka 1994).

Formal Sector Employment

Unpaid work and family responsibilities. as well as lack of investment in women's education. are strongly associated with women's relatively low rates of participation and their limited earnings in formal sector labor. Women's participation rates usually dip in the childbearing years, and earnings tend to decline following an interruption in employment. Younger on average, work more hours than older women, and married women with young children tend to work less than childless women and mothers of grown children. The correlation of marriage and childbearing with labor market outcomes can be seen even in industrial countries, where wage differences between married women and men are larger than those between single women and men Similarly, in some developing countries relative earnings decline with age (table 2.2) Children are not the only treason for interruptions in women's labor force participation; caring for ill or aged family members is often a woman’s responsibility. A study from Hungary estimates that half of all absenteeism by women workers is the direct result of the need to care for sick relatives (Einhorn 1993).

In Countries, Single Women Earn More Than Married Women and Younger Women More Than Older Women.

Table 2.2 female-male earnings (adjusted for hours worked) by marital status and age (percent)

|

Country |

Female-male |

Earnings ratio |

|

By marital status |

Married |

Single |

|

Australia |

69 |

91 |

|

Austria |

66 |

97 |

|

Germany |

57 |

103 |

|

Norway |

72 |

92 |

|

Sweden |

72 |

94 |

|

Switzerland |

58 |

94 |

|

United Kingdom |

60 |

95 |

|

United States |

59 |

96 |

|

Age |

A 25 |

B 45 |

|

Brazil |

75 |

63 |

|

Colombia |

94 |

70 |

|

Indonesia |

81 |

60 |

|

Malaysia |

82 |

61 |

|

Venezuela |

92 |

70 |

Sources: Blau and Kahn 1992 Sedlacek Gutierrez. and Mohindra 1993

Thus. women s labor market outcomes can be substantially poorer than those of men because women's employment opportunities are constrained by social arrangements at the family or household level. These social demands are reinforced by legal conventions. Within the labor market itself, social or employer discrimination can affect women and men differently. and these differences are reflected in the resource allocation decisions taken within the household. Although wage discrimination is illegal in many countries, employers may respond to an increase in the supply of workers by segregating jobs by gender or offering less training to women who they perceive as being temporarily attached to the labor force (even if in fact most women never drop out). For example, women in the former Soviet Union are fairly well educated and have high labor force participation. but they are concentrated in occupations requiring fewer skills and less vocational training than men, and, on average. they earn less than men (Fong 1993).

Female Wages Are Lower than Male Wages, but This Is Changing.

Table 2.3 female-male earnings ratio over time Female-male earning 1 ratio (percent)

|

Country |

First observation |

Second observation |

A v Average annual percentage change |

||

|

Brazil |

50.2 |

(1981) |

51.6 |

(1990) |

0.7 |

|

Colombia |

67.2 |

(1984) |

70 2 |

(1990) |

0.7 |

|

Côte d'Ivoire |

75.7 |

(1985) |

81.4 |

(1988) |

2.4 |

|

Indonesia |

55.6 |

(1986) |

60.0 |

(1997) |

1.3 |

|

Philippines |

70.9 |

(1978) |

80.0 |

(1988) |

1.2 |

|

Thailand |

73.5 |

(1980) |

79.8 |

(1990) |

0.8 |

Note: Monthly earnings for Indonesia and Thailand rural and urban: for all others urban only

Source: Tzanntors 1995

Women's earnings relative to men's tend to increase over time. A study of six developing countries shows that female earnings relative to male earnings increased by 1 percent a year in the 1980s (table 2.3). There were two reasons for this increase: over the years women entered higher-paying sectors. and within sectors, their pay increased in relation to that of men. This gain would have been even greater had it not been for the effect on wages of increased female participation in the labor force. However, the most visible dimension of gender inequality in the formal labor sector remains the wage difference between men and women. Women's wages are. on average lower those of men by about 30 to 40 percent.

Social or employer discrimination can affect women and men difference and these difference are reflected i/? the resource allocation decisions taken within the household

A recent study of the gender wage gap in Russia shows that after controlling for education differences, the ratio of women's to men's average hourly earnings stands at just over 71 percent: it has remained at that level since the 1960s. Part of the reason for women s lower hourly earnings in Russia and many other countries lies in patterns of occupational segmentation by ,gender. Some analysts argue that women-who do most of the household work in Russian households and also have high participation in the formal labor market cope with the burdens imposed on them by taking less demanding work and devoting less time to advancing their careers (Newell and Reilly 1994).

Informal Sector

One difficulty analysts face in interpreting trends in women's labor force participation and employment in developing economies is the large number of women engaged in informal sector activities, many of which overlap with subsistence - orientated household or community-based activities. Informal sector employment in most developing countries. whether in microentreprises or in casual work, is an important source of livelihood for women and their households.

The L competitiveness of women's informal sector activities is constrained by women's limited mobility and lack of access to financial and public sectors.

A recent study in Mexico estimates that 41 percent of the work force in Mexico's major-cities is employed in the informal sector (World Bank 1995c). Data from a 1989 survey show that 60 percent of men working in the sector are salaried workers' compared with only 18 percent of women. By contrast. 80 percent of women working in the sector are unpaid family members, as against 27 percent of men. By far the most common activity in the informal sector is commerce (fixed-location or itinerant), followed by repair works food preparation. and sales, and small-scale manufacturing. The sectoral distribution of informal employment reflects the hey role informal workers play in supplying goods and services to low-income consumers. Women tend to be concentrated in commerce and men in services and manufacturing, although the percentage differences are relatively small. Two generalizations can be made on the basis of this study: informal sector workers earn less than workers in large firms and women earn less than men.

Another recent study of tour communities in Lusaka. Guayaquil (Ecuador), Metro Manila, and Budapest shows that informal sector activities ate especially important for during periods of economic reform Although the numbers both of men and of women in the labor force tend to increase during these times women rely more on the informal sector than men clot The competitiveness of women’s informal sector activities is informal by women's limited mobility and lack of access to financial and public services. Women also tend to specialize in non traded goods and services that show relatively low average returns to labor. Across the tour cities in the study, women earn between 46 and 68 percent of men's wages (Moser 1994)

The ability of informal sector workers to increase their returns depends on access to physical and human capital and their relationship to the institutional and regulatory environment. Contrary to the common belief, many microenterprises face considerable costs associated with the regulatory environment, including registration and licensing fees, as well as outlays for contracts with public authorities concerning zoning regulations and use of public utilities. In Argentina regulatory costs are estimated to absorb as much as 21 percent of the average microfirm's operational expenses. In some sectors, such as manufacturing and construction, the costs of regulation are about 44 percent (World Bank 1994d). In Mexico real regulatory costs. including the costs of compliance and evasion, are about 20 percent of total costs.

Regulatory costs also inhibit Job creation in the informal sector. In Argentina across-the-board deregulation could generate as many as 170,000 jobs in small-scale manufacturing alone. Furthermore. poor workers in family-based firms or micro enterprises and particularly women entrepreneurs-often lack access to such basics as water and power. Targeting infrastructure investments to the poor, which takes account of the needs of women entrepreneurs s. can significantly enhance their productivity and earnings.

In rural area where formal markets often are not well developed. informal employment activities play a vital role. In Asia the proportion of female rural wage laborers increased sharply in the 1960s and 1970s. In India women make up a larger proportion of rural wage laborers than of the entire labor force, probably because of growing landlines and poverty among rural households. Rural household labor accounts for a disproportionately large share of employment among the poor and an even larger share among women. Furthermore, a larger proportion of female than male laborers are hired on a casual basis, largely because family arrangements, especially lack of control over property, limit women's ability to work (Hart 1986: Bardhan 1993). Low status in the labor market is also linked to low female indicators in education, health, and nutrition.

Providing credit directly to women has a positive effect on household and individual welfare and improved gender equality.

Social norms affecting decisions within the family about occupational choices or migration can also lead to differential patterns of male and female earnings in informal markets (Bhiswanger and Rosenzweig 1984). Family responsibilities hinder women's geographic mobility, constraining their ability to command high wages and limiting them to certain areas or industries. The concentration of women in certain sectors, especially nontraded goods and set-vices. intensifies competition between women entrepreneurs and wage workers and lowers the returns to female labor. These effects are compounded by women's lack of access to credit. training, and technology.

(fender Inequality in Access to Assets and Services )

Access to Financial Markets

The availability of financial services and access to them are considered important for several reasons. First. savings provide a kind of self-insurance. Second, credit helps households maintain a certain level of consumption at those times when their income fluctuates temporarily. Third, credit can be used to fund investments in capital or other inputs that will yield relatively high returns to production. if households cannot finance such investments from their own savings. A fourth and no less important reason is the role of savings and credit in increasing household members' options outside the home.

Inequalities between women and men in access to financial services- particularly credit--are widely documented. Collateral requirements, high transaction costs. limited mobility and education, and other social and cultural barriers contribute to women's inability to obtain credit (Holt and Ribe 1991). The implications tot household efficiency and individual well-being differ, however, depending on whether the household pools its financial resources. If, as the unitary household model assumes. a household pools its resources the characteristics of individual borrowers are less important than if there is little or no pooling. In the first case. credit resources will be used to meet household needs that have been jointly determined, regardless of who the borrower is. In the second case, the use credit is put to and the needs it then satisfies depend on which household member is borrowing.

A recent study of credit programs in Bangladesh sponsored by the World Bank shows that providing credit directly to women has a positive effect on variables typically associated with household and individual welfare and improved gender equality (Pitt and Khandker 1995). The study looks at three programs in Bangladesh: the Grameen Bank. the Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee (BRAC), and the Bangladesh Rural Development Board (BRDB). in 1992, women accounted for 94 percent of Grameen Bank members. 82 percent of BRAC members. and 68 percent of BRDB members (Khandker and Khalily 1995; Khandker, Lavy, and Filmer 1994). Only the results for the Grameen Bank are presented here.

Table 2.4 presents the impact of credit obtained by women and men on a variety of social and economic indicators. The results show a clear and positive impact of both male and female borrowing on all indicators of Toward gender equality family welfare especially through an increase in per capita expenditures increases in both boys' and girls schooling, anti a reduction in fertility. Females borrowing has a greater effect on girls' schooling anti per capita expenditure than does male loot-rowing: male borrowing has a greater effect on boys' schooling and fertility than does female borrowing. Interestingly. female borrowing also results in mote female ownership of nonoland assets and an increased supply of female labor to cash - income -earning activities (Pitt and Khandker 1995).

Loans to Women and Men Have Important Welfare Implications.

Table 2 4 welfare effects of Grameen Bank loans (percentage increase)

|

Welfare e change |

Effect of male borrowing |

Effect female borrowing |

|

Increase in boys' schooling |

7.2 |

6.1 |

|

Increase in girls schooling |

3.0 |

4.7 |

|

Increase in per capital expenditure |

1.8 |

4.3 |

|

Reduction in recent fertility |

7.4 |

3.5 |

|

Increase in women's labor supply to cash-income earning activities |

0 |

10.4 |

|

Increase in women nonland assents |

0 |

19.9 |

The introduction of programs such as the Grameen Bank in a village has a positive effect on agricultural and nonagricultural production (Khatidketati Chowdhuty 1994: Rahman and Khandke 1994 The probability that women will be self-employed rather than work for wages increases by 52 percent. The latter finding is important because much of the wage employment open to women in rural areas is very poorly remunerated and can be quite exploitative. Self employment can bring the opportunity of higher returns for women, plus the freedom to integrate their earning activities into other work as they see fit.

Access to financial services alone cannot reduce gender inequalities in the allocation of household resources. A qualitative study reviewing several targeted credit programs in Bangladesh cautions against overgeneralizing about the benefits of giving women access to credit. The study finds that it is difficult to infer that increased borrowing alone improves women's bargaining power because in many rural Bangladesh households the question of who controls the resources is quite complex (Goetz and Sen Gupta 1994). Nevertheless. the possibility of receiving credit (or similarly of working for wages) may give women greater bargaining power within the household. This bargaining power can be used to improve child health and nutrition and may increase the likelihood that children will attend school.

Access to Lund and Property

The ownership of land and the distributions of land rights influence the productivity of labor and capital resources and the incentive to invest in resource management Private property rights. in particular. are associated with increased access to product and factor markets. especially credit markets. and to public services such as public utilities and agricultural extension. However. relatively little direct evidence exists to link independent owner of land by women with increased access and productivity. One obstacle to empirical work is that women s access to land and property is often mediated trough marriage (A married woman land rights are frequently limited to use rather than ownership.) Future more. complex systems of land tenure make it difficult to generalize about the effects of owner ship on productivity. None some evidence suggests that independent land rights for women could enhance both the efficiency with which resources are used and the well-being of women and their households: (Agarwal 1994).

The possibility of receiving credit may give e women greater bargaining power within the household which can be used to improve child health and nutrition.

While independent land rights may increase efficiency and household welfare, lack of secure land appears to be associated with low investments by women in land conservation. In Zimbabwe's communal areas, land that a women acquires is often allocated to her only temporarily: for example, the location of land allotment received from husbands or borrowed from neighbors is usually subject to periodic change (Jackson 1993). The same is true in parts of West Africa (David 1992 Jackson 1994). Uncertainly about the permanence of their control over the land means that women may be reluctant to invest in improvements that will benefit the landowner rather than the user.

A significant trend in recent decades in developing countries has been the move toward private ownership In some countries this trend has been encoulagecl by reforms dealing with land redistribution tenancy or land titling Such reforms are considered important for promoting long-term investments and the adoption of the latest technology They also provide the collateral people need to gain access to credit and other factor markets Ironically, evidence also suggests that perform inequalities in male and female land rights are reinforced by land reform programs For example, in Latin America most reforms are based on the premise that the man of the household its the household head. This presumption means that women (except for widows and ownership. Even where women and men benefit equally from land reform differences exist between nominal and real land rights (see box 2.3).

In the central part of European Russia and in Moldova the lands and assets of state and collective farms are being parceled out in allotments as part of wider economic reforms. Every person who lived and worked on a collective farm receives a share of the land Data show that although on average, women have received a slightly higher proportion of land shares than men, the nonland capital assets of the old farms ale being distributed as property shares on the basis of a formula heavily weighted toward an individual's wage rate and years of employment. Such criteria favor men over women and give men more valuable property chares. Dividends paid on these property shares also tend to be higher than those paid 011 land shares Holt 1995).

Land reform programs that fail to account for gender differences in rights

|

Box 2.3 who gets access to land? Honduras and Cameroon Honduras' Agrarian Modernization Law of 1974 includes a provision giving men age 16 or older the right to access to land, independent of any other qualification. For women. however, this right is restricted to unmarried mothers or widows with dependent children. Furthermore. if a male beneficiary dies or becomes incapacitated. the law gives preference in inheritance rights to a male child over the child's legally married mother. Some 30 percent of rural Honduran households are headed by women at least part time because of the seasonal migration of men to look for work (Saito and Spurling 1992). |

In the northwest and southwest provinces of Cameroon. an estimated 50 percent or more of those who claimed land within the first ten years of land registration (1974-85) were classified as public servants. Over 32 percent of all the remaining land titles went to businesses.

Women make up more than 51 percent of Cameroon s population and do more than 75 percent of the agricultural work. but they are virtually absent from land registers. Only 3.2 percent of all land titles issued in the Northwest Province were given to women; in the Southwest Province the figure was 7.2 percent. For the country as a whole. it is estimated that women obtained under 10 percent of all land certificates (World Bank 1995a). to own. use, and transfer land may actually exacerbate the insecurity of women's land claims and. as a result, harm household welfare. For example, there is evidence that land titling focused on male household heads has adversely affected women's ability to farm independently. Moreover. intrahousehold inequalities in income and decisionmaking have increased (FAO 1993) In Africa some titling programs have allowed men to take advantage of their control over land to redesignate land formerly cultivated by women as household land. This switch provided the opportunity for men to increase the amount of work they expect from women on household plots. In other cases women have received smaller and less fertile plots than they had before for their personal crops (FAO 1993).

Recognizing women's independent claims to land is therefore an important issue in property reform. In poor households. having rights to land could alleviate both women's own poverty and the household's risk of remaining poor. The season is mainly that women s access to economic resources has a positive effect on household welfare (Agarwal 1994). From the point of view of efficiency, secret land tenure increases the incentive to manage resources efficiently and expands access to formal credit markets. Because secure land tenure can mean greater productivity, it may also increase the household's incentives to invest in women's human capital.

Access to Extension Services

Agricultural extension services provide information training and technology to agricultural producers. Extension services have always been regarded as necessary for agricultural modernization. Given the importance of women's labor to agriculture in most regions, providing women with access to agricultural extension services is essential for current and future productivity. Types of agricultural extension services vary, hut in most countries publicly provided services dominate. Evidence suggests that women have not benefited as much as men have from publicly provided extension services.

Given the importance of women's labor to agriculture it is in most regions providing women with access to agricultural extension services is essential for current and future of productivity.

A review of five African countries shows that extension agents are most likely to visit male farmers than female farmers (table 2.5) The impact of this inequity on female productivity depends in part on whether women and men within households pool information. There is, however. little evidence to suggest that this happens (see box 2.4). It is important to ensure that extension services reach omen directly, not only to redress gender inequalities but also to maximize productive efficiency. omen play a critical role in production of food and cash crops for the household. in postharvest activities. and in livestock care Men and omen perform different tasks they can substitute for one another only to a limited extent. and this imitation creates different demands for extension information Also, as men leave farms in search of paid employment ill urban areas. women are increasingly managing and operating farms on a regular and full-time basis. Hence. omen are becoming a constituency for extension and research services in their own right (World Bank 1994e)

Table 2.5 visits by agricultural extension agents (percentage of households visited)

|

Country and year |

Households with female head |

Households with male head |

|

|

Kenya. 1989 |

112 |

9 |

|

|

Malawi, 1989 |

70 |

58 |

|

|

Nigeria 1989 |

37 |

22 |

|

|

Tanzania, 1984 |

40 |

20 |

|

|

Zambia |

|||

|

1982 |

57 |

29 |

|

|

1986 |

60 |

19 |

|

|

Box 2.4 do women farmers learn from their husbands? A survey of women farmers in Burkina Faso found that 40 percent had some knowledge of modern crop and livestock production technologies. For most of these women, relatives and friends were the source of information; nearly one-third had acquired their knowledge from the extension service, and only 1 percent had heard of the technologies from their husbands. Men are less likely to pass information on to their wives when crops and tasks are gender specific. In Malawi women claimed that their husbands rarely passed on advice to them: if their husbands did tell them something. the women did not find it relevant to their needs. In India women learned from friends, relatives. neighbors. and sometimes from their husbands. but this second-hand information seldom changed their production patterns (Saito and Spurling 1992). |

The expansion of agricultural services beyond the public sector is a growing phenomenon in developing economies. The inadequacies of public funding plus the need to provide snore client-oriented services, suggest that the private sector has an important role to play However, women's limited access to land and credit put the many potential benefits offered by extension services out of reach. For example in Kenya's Meru and Maranga areas more than half the women surveyed cited a shortage of cash as their reason for not adopting, technologies that would maximize their output and increase their efficiency. The amount of education omen receive and the efficiency with which they run their farms are also closely linked This tie is particularly significant in light of the fact that one purpose of extension services is to advise farmers on use of modern technology.

Three studies of Kenya found that the gender of the farm manager was, by itself. an insignification factor in output per hectare but that the manager's educational level had a significant effect on farm productivity (Moock 1976: Saito and Spurling 1992: Bindlish and Evenson 1993). Simulations based on these studies suggest that significant gains could accrue to increased investment in women's physical and human capital. As the data in table 2.6 show, if women and men shared the same educational characteristics and input levels. farm-specific yields would increase between 7 and 22 percent. Giving women primary schooling, by itself. would increase yields by 24 percent. Thus under investment in women's education limits growth of agricultural productivity. Well-targeted extension services can help to narrow the differences in productivity that arise from educational inequalities (Schultz 1988)

Increasing Human Capital and Input Levels Would Increase tile Yield for Women Farmers.

Table 2.6 effects of increasing women farmers' human capital and input levels Increase yields

|

Policy experiment |

(percent) |

|

Maize farmers Kenya, 1976 |

|

|

Effects of giving female farmers sample mean characteristics and input levels |

7 |

|

Effects of giving female farmer s men's education and input levels |

9 |

|

Effects of giving women primary schooling |

24 |

|

Food maize (maize beans and cow pears) farmers |

|

|

Effects of giving female farmer men's education and input levels |

2.0 |

|

Effects of increasing land area to male farmers' levels |

10.5 |

|

Effects of increasing fertilizer to male farmers' levels |

1.6 |

Conclusion

Analysts must look beyond market outcomes to identity the sources of persistent inequality between women and men. The search must focus on the household and its role in the formation of present and future human capital and on institutions beyond the household that reinforce and perpetuate gender inequalities. Gender inequalities within the household affect market outcomes, and these feed back; into household decisionmaking. This process is reinforced by inequalities in access to assets and services beyond the household. Improving the relative status of women within the household and increasing their access to assets and services will increase the returns to investment in human resources and improve the prospects for sustainable economic growth.

We must look for that which we have been trained not to see Ann Scales, Yale Law Journal 1986