| The Courier - N°160 - Nov - Dec 1996 - Dossier Habitat - Country reports: Fiji , Tonga (ec160e) source ref: ec160e.htm |

| Dossier |

| Habitat |

Habitat

Livable cities and rural rights

(Dossier coordinated by Debra Percival and Claude Smets)

The United Nations Conference, Habitat 11, on human settlements (Istanbul, June 3-14 1996) exposed the Herculean task of addressing the problems of ever-growing cities and called for 'shelter for all.' The special contribution of civil society in making cities more liveable was acknowledged at the conference - but the big question is, who will foot the bill ? The meeting also spoke of improving dwellings in rural areas to keep people on the land and halt the mass exodus to the cities. But the right to remain and prosper from one's habitat can be at odds with outside pressures for environmental conservation. The dossier looks at some of the issues raised by the conference, and the wider significance of 'Habitat II'

The second UN gathering on the theme of 'habitat', staged two decades after the first conference in Vancouver, took place against a backdrop of rapid and alarming urban growth. In 1900, one person in ten lived in a city. By 1948, the ratio was three in ten and by the year 2000 half the world's population are expected to be urban dwellers. 25 years after that, the figure is expected to have climbed to 60%. Africa is the region that currently has the highest rate of urban growth. In 1950, it had only one city with a population of one million. By the end of this decade there could be 60 cities of this size, according to UN figures.

The focus on human settlements and liveable cities inevitably meant that Habitat II covered some of the same ground as other UN conferences convened during the 1990s to explore the big issues facing mankind: the 1992 'Earth Summit' on environmental matters in Rio de Janeiro, the 1994 Population Conference in Cairo, the 1995 Social Summit in Copenhagen and the 1995 Women's Conference in Beijing. Issues common to all the agendas included rapid population growth, environmental degradation, access to clean water, poor sanitation, lack of infrastructures, and women's issues.

The rallying calls of Habitat II, set out in the Conference's conclusions, were 'shelter for all' and 'sustainable human settlements in an urbanising world.' The Nairobi-based Centre for Human Settlements is to be the focus for the follow-up. But as delegates dispersed, one of the pressing questions was where the money will come from to meet the host of agreed objectives - which include clean water with improved technology, conservation and protection of the environment, and better health and education. In this dossier, European Commission officials from the Development Directorate General, who attended the conference, reflect on Istanbul and its likely followup.

Whereas in the past, cities were associated with economic development, innovation and the diffusion of new ideas, nowadays they conjure up the vision of urban poverty, environmental degradation, poor sanitation and a host of health hazards. Urbanisation is the direct consequence of rapid population growth, according to the 1993 Human Development Report. In 1965, agriculture provided 77% of employment in developing countries and represented more than 41 % of Gross Domestic Product. By 1985, this sector was contributing a lot less to GDP but was still providing 72% of all employment. So a large number of people continue to depend on agriculture although its share of the global economy is declining. In these circumstances, it not surprising that many of the world's poorest people are migrating to cities - the annual estimate is 20-30 million.

The dossier looks, in particular, at the environmental cost of rampant urbanisation and at the problems of city living for more vulnerable groups such as women. They are often among the poorest urban dwellers and can fall victim to exploitation and crime.

Paradoxically, poor people in cities are becoming even poorer as economies improve. Additional pressures on these marginalised groups living in cities are neatly summed up by Jeremy Seabrook, author of 'In the Cities of the South.' In a recent article for Gemini news agency: 'Tougher Struggle for Survival in the Concrete Jungle,' he writes; 'As the pace of development quickens, with high economic growth and increased migration to urban areas, land price in most big cities have soared. Poor people are being increasingly removed from their hoary" - by mysterious fires, explosions and 'accidents'. Meanwhile, the urban poor's ability to mobilise and achieve has been used against them. The capacity of people to create homes and secure local communities has been used as a justification for the withdrawal of government services.'

He continues: 'As inequalities become more glaring, enclaves of prosperity are sealed off from the slums by checkpoints, guards and fences - like frontiers to another country. Despite this, people are still flocking to the city - often refugees from intensifying, industrialised agriculture and.. megaprojects in the countryside...' Mr Seabrook points out that without decent jobs, they fall prey to sub-contractors, who exploit them, offering them low pay and demanding that they work long hours.

Civil society

In the cities of many developing nations, 'civil society' is taking a lead, with projects to bridge the gap between the 'haves' end the 'have note'. Numerous participants at the Istanbul conference applauded the urban programmes undertaken by various elements of civil society, which include NGOs, community groups and individuals. Their significance was recognised in Istanbul, where their voice came through loud and clear. Nigerian journalist, Paul Okunlola, writing in this dossier notes a move towards 'bottom up' projects in Lagos as a result of the tough times.

Agostinho Jardim Gonçalves, the President of the NGO-EU Liaison Committee, was particularly pleased at the input of civil society to the conference's committees and conclusions. The debate, he said, had not just been about the macroeconomic aspects. Instead, it had come 'within the reach of the populations themselves.' The people, he argued, were both victims of the anomalies of inhumane settlement and the key players in efforts to construct a humane, dignified habitat.

Jeremy Seabrook describes some of the inspiring international initiatives undertaken by civil society. Examples include the Society for the Promotion of Area Resource Centres (SPARC) in Bombay, which works with pavement dwellers; the Association of Basic Needs (ARBAN), and 'Health for All' in Dhaka; the Eddie Guazon Foundation in Manila, which seeks to protect the poor against private interests; and the Foundation for Women, which is trying to tackle the trafficking of girls for Bangkok's brothels. But Mr Seabrook also warns against overestimating the strengths of popular organisation. As he points out: 'They require an enabling and positive framework, which the free market can never provide. Government intervention, of a more benign and positive kind than hitherto, is vital if people are to help themselves. As it is, too often they are forced to struggle against the people elected to govern them.'

The chair of the Habitat Conference, Wally N'Dow, emphasised local solutions. The conference, he said, 'recognised the changing global patterns of life' and that solutions must be found at the local level. 'National governments and international agencies', he argued, were not in a position to solve massive urban problems or to pay to put them right.

There were a number of donor pledges at the conference. The European Union countries, for example, reiterated their long-standing commitment to provide 0.7% of GNP for development by the year 2000 - though many of the 15 member states are still well short of this target.

One scheme which has attracted the particular interest of donors is South Africa's Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP). To a considerable extent, the success of President Mandela's government is likely to be judged on the success of this programme. It aims, among other things, to improve health, education, housing and sanitation and as such, it mirrors many of the 'Habitat II' goals. Launched in 1994, it is the centrepiece of the South African government's efforts to create a more democratic, prosperous, non-racial and non-sexist society. In the dossier, we look at the RDP's objectives, how it is faring and what sort of support the EU is giving.

Rural rights

Beyond the city, the dossier looks at what is happening to some rural dwellers who have not taken flight to the city. Although, largely focused on the city, Habitat II acknowledged the importance of urban and rural linkages in its conclusions: 'Rural and urban settlements are interdependent... governments must work to extend adequate infrastructure and opportunities to rural areas to increase their attractiveness and thereby minimise... migration.' There was mention too of the need for more jobs and housing for rural areas.

But in some rural areas, the inhabitants have found themselves in dispute with conservationists. The latter seek to protect wildlife and the rural habitat by setting up national parks - a solution which is not necessarily in the interests of local people struggling to maintain their livelihood. We take a look at such dilemmas and the possible solutions being developed so that rural dwellers can continue to make the most of their habitat. This rural struggle, where solutions are also being called for at a local level, is not unlike the battle being waged for a better quality of life in the cities.

Towards a global concept of urban development - an interview with Daby Diagne

Deputy mayor of the city of Louga, Daby Diagne is also President of the Finance Committee of Senegal's National Assembly, General Secretary of the Association of Mayors of Senegal and President of the World Federation of United Cities. He is the ACP-EU Joint Assembly's General Rapporteur on urban development and The Courier had the opportunity to interview him in September at the Assembly's meeting in Luxembourg.

· You have just submitted an initial report on urban development to the Joint Assembly. In it, you recommend that the Community adopt a specific and consistent global policy in this field, notwithstanding the fact that successive Lomé Conventions have contained a number of significant provisions relating to the subject. What is the reasoning behind your recommendation ?

- There are several reasons. First, there is the fact that, in the past, cities were often viewed solely in terms of infrastructures and sectors. Experience shows that this approach is not effective. Specialists are increasingly opting for a more global 'city' concept. The Commission must therefore adapt itself to the new situation. It is true that it has financed infrastructures and launched health and clean-up programmes, but the problem is that this has been done in a somewhat unsystematic way without being linked to long-term regional development or a zonal policy. There is now an increasing need for an integrated regional development approach.

· Do you think ACP countries are aware of the importance of cities ?

That's another question altogether. Obviously, the ACP countries are in the process of changing their views on this subject and a number have appointed ministers to look after urban affairs. The reality of city life has to be taken into account. The rate of urban growth in the ACPs far exceeds that in other parts of the world and it is in the towns and cities that one sees the most glaring instances of poverty and under-development. People have therefore been forced to take the 'city' phenomenon into account in the ACP countries.

· The political will must exist for a policy to be successful. Do the ACP countries have a genuine will to implement an urban policy ?

- I don't think it is possible to speak of a uniform trend in all ACP states. However, in certain regions - for example in West Africa, which I know well - a municipal culture is beginning to take shape. There is a growing political will, which is illustrated by the discussions on decentralisation, and people are increasingly recognising that central government cannot do everything by itself. One can find regional development and planning policies designed to create the fabric of mediumsized cities. Not everyone has them but it is something we are seeing more and more of.

· ACP countries face complex challenges and there are people who say that the actions of the European Community are too dispersed owing to the number of sectors it is involved in. Doesn't your recommendation simply add to this problem ?

- On the contrary. I regard my recommendation as being pro-integration and therefore pro-globalisation - which is not the complete opposite of a sectoral, diversified approach. I believe it would allow the Union's activities in certain fields to be better interlinked. I am thinking here of water, health, clean-up operations and infrastructures - all of which are major problems for society. Naturally, a more global concept will require greater dedication, and if there are additional resources, so much the better, but, in my view, the situation could be improved even with what we currently have available.

· The rate of urbanisation in Africa is higher than elsewhere and the living conditions of city dwellers - particularly those in the shanty towns - are becoming increasingly difficult in terms of health, education, environment and so on. What, in your opinion, would be the optimum strategy for reversing the decline, at least in the short-term ?

- First of all, I think we have to make a distinction here. Let's take the actual rate of urbanisation. Contrary to what is generally thought, this is lower than in the rest of the world. In other words, Africa has fewer towns and cities than the rest of the world. It is the rate of growth in the urban population that is higher. Populations are becoming increasingly concentrated in the cities, with the drift of people from the countryside. In addition, the phenomenon is being fed by demographic trends. You ask me if there is anything we can do to halt this. There are actions that can be taken to restore some balance. For example, we could make investments in the rural environment to keep people in the countryside, and we could implement suitable agricultural policies.

But we must not labour under too many illusions, because life in towns and cities will be an inevitable characteristic of the next century. Economists and urban planners have been considering the phenomenon for a long time now - perhaps 30 or 40 years. It is something that cannot be halted, because it is a fact of civilisation. So, what should we do? Above all, we should devote our efforts to regional development, achieving a balanced distribution of human resources, and a more equitable exploitation of natural resources. Power has to be decentralised so that people do not abandon their roots but face up to local challenges. And we have to implement urban policies which are satisfactory in terms of investment, management and popular participation. In simple terms, urbanisation has to be managed. We cannot hope to reverse the trend overnight, particularly in the case of a continent like Africa where everything happens quickly. Africa is enormous and its population has not yet reached its maximum levels. We have to take all this into account.

We must acknowledge that scientific progress and improvements in the field of health have contributed to population growth, and a reduction in mortality rates. This means that urban civilisation is a reality that we have to manage. There is a risk of uncontrolled growth in urban centres. When infrastructures are lacking, when there is no water, when hygiene cannot be guaranteed and when there is no work, a country's security is threatened.

· You have mentioned democracy end the decentralisation of government This also requires adequate financial resources. Where do you think the ACP countries will find the money to implement decentralisation strategies ?

- Democracy involves a search for freedom - freedom of opinion and expression, independent of material or financial problems. The problem with decentralisation lies in administrative method. It is not purely a matter of money. In the first instance, it is a question of choosing the right approach. It has been demonstrated that without any extra resources, one can still act differently by delegating and decentralising. And success is much more likely because the people are involved in the process. Admittedly, it requires an internal reallocation of resources. A proportion of everything that was formerly centralised has to be allocated to development and to basic needs.

To answer your question more directly, there is a great deal of talk of this alternative method of governing. It is inspiring new hope and a thirst for something better. It is even being viewed as an 'ideal' solution - which it cannot be entirely. However, by decentralising human and economic resources, and by allowing people to participate, hope can be inspired at local level. This should make for better administration and support, which is an improvement in itself. Of course, this may make people more demanding. Will it satisfy their requirements? As I have already said, internal resources will have to be reallocated, but resources must also come from outside. One cannot make an allout effort for decentralisation without doing something to improve international cooperation. This cooperation, however, must be adaptable, and the state must retain its pre-eminent position and its role as guarantor and arbiter. But in addition, local communities should have access to international cooperation either directly or indirectly through their organisations, municipal structures and so on.

· In this context, what role do you see for international organisations - not just in terms of financial resources, but also of human resources ?

- I think what we now need to do is build up a pool of skills in each municipal area. The developed countries have experience in this field. We have to take their processes as a model without necessarily copying their experience. This is something which will be discussed. Secondly, in the context of relationships between towns and cities, I believe it is possible to make access to experts more flexible and that this can take place very quickly, with the provision of training and fairly basic technology transfers. General training is also extremely important. In order to build up a pool of skills in towns and cities, local government must form a dynamic, management-oriented team. The approach has to be one of business-like management and objectives have to be targeted using private-sector methods, although public-service requirements always have to be borne in mind. A great deal, therefore, can be done at international level, in terms of support for networks of associations and committees of locally elected representatives, enabling them to discuss matters.

We could, for example, carry out a comparative study of legislation in a particular area, thereby gaining access to other types of experience. Internationally, aid can be given to associations to help them buy equipment and attain a degree of freedom of manoeuvre vis-à-vis the authorities. In the field of decentralised cooperation, the international community can help elected representatives to implement their projects through partnerships, conducting studies, and providing personnel. Cooperation is possible in all spheres - implementation, management, financing and so on. I believe that a new type of cooperation will gradually come into being. It is not a question of creating 'white elephants', but rather small and medium-scale projects which are of genuine use to the population. And I am not talking here about acts of charity, such as the donation of medicines, but sustainable projects.

Habitat II: taking stock

by Christian Cure'

The future of towns and cities is not what it was. In the 20 years between the first United Nations conference on human settlements (1976) and Habitat II which took place in Istanbul in June 1996, the situation has changed a good deal. The significance of urbanisation - and its irreversible nature - are now acknowledged, as is the powerlessness of the authorities to deal single handedly with the complex phenomena which result The author of this article points out that civil society has suddenly broken into a field hitherto the preserve of official agencies and qualified experts, claiming a 'right to the city' based on research into more equitable development models.

Vancouver to Istanbul: two symbols for two eras

Vancouver was the 1976 host of the first conference on human settlements organised by the United Nations. At that time, the UN was celebrating 30 years of existence and Vancouver, a model of urban development and modernity, provided inspiration for the developers and experts needed to plan the cities of the future. 'Appropriate technologies' heralded the possibility of mass-produced, cheap housing for everyone.

Twenty years later, the UN chose Istanbul as the host city for the Habitat II conference on human settlements, forcing us to face up to a quite different situation: uncontrollable urban growth (400 000 migrants arrive there every year), social and environmental problems, and intercultural and political tensions (amply illustrated by the Turkish politicians' inability to form a government at the very time the Conference was taking place). In brief, Istanbul presents us with the usual list of problems facing most of the world's major cities - and those of developing countries in particular.

Against this backdrop, the international community - 180 countries, 500 local dignitaries, a few thousand professionals and even some ordinary citizens - came together from 3 to 14 June to discuss a 'settlement action plan'. This document, which had been in preparation for two years, contains 183 articles. It sets out a series of goals, principles and undertakings as well as providing an action plan for cities, the initial results of which should begin to be seen by the year 2001.

The preparatory committee selected two basic topics for discussion: securing adequate shelter for all, a basic but nonetheless controversial theme; and sustainable urban development The latter encompasses housing, demographic factors, infrastructure, services, the environment, transport, energy, social and economic development, the future of underprivileged groups and combating exclusion.

The cycle initiated at the Rio Earth Summit in 1992 (followed by the Copenhagen, Beijing and Cairo meetings) was continued by Habitat II. Two major handicaps had to be overcome - 'conference fatigue' (with the resulting fact that there were fewer delegates than anticipated) and ensuring that what had been accomplished at earlier conferences was not undermined. Given that the subject of the meeting was human settlements, it was inevitable that sensitive issues already debated at previous summits, relating to the environment and social aspects, would keep recurring.

Civil society as an active force

A number of conclusions arose from the official sessions (hearings, dialogues and various forums) which took place over the two weeks of the conference.

First, Habitat II represented a recognition of the fact of urbanisation. In the past, there was a tendency on the part of the international community to play down, or even ignore, the phenomenon of urban growth and this was reflected in the meagre resources allocated to this area by donors. Today, the issue is better understood than it was 10 or 20 years ago, and it is acknowledged that the growth trend is unstoppable. Statistical studies and a set of 'urban indicators' drawn up for Habitat II confirm the scale of the problem.

Second, the Istanbul summit was a lesson in modesty. The obvious powerlessness of public authorities to deal single-handedly with the challenge of burgeoning towns and cities is recognised. The result was an understanding that a more pragmatic view is needed - one which pays more attention to the complexities of urbanisation, to the wide variety of possible responses and, above all, to the multi-faceted nature of the players involved.

The Conference therefore became a genuine forum for debate. One of its most significant aspects was the emergence of 'civil society' as an active force. Hitherto, the field has largely been the preserve of official agencies and qualified experts. For the first time in a UN forum, local authorities, community leaders, private sector representatives and other dynamic forces in civil society were invited to give their views and take part in discussion groups. Whereas in the past, the debate was dominated by macroeconomic and technical questions, in Istanbul, the political and social aspects were given prominence as well.

The effect of this was to improve the quality of the debate. The outlines of a new relationship between governments and civil society (NGOs, ordinary citizens and popular urban groups) were defined - with the local authorities slotting in somewhere in the middle. And there was a particular focus on the question of dimension or scale: what should be the basis for urban democracy and citizenship. Both of these are seen as essential if one is to have successful and sustainable urban development policies.

A right to the city?

The first stage of the analysis is to look at urban life from a macroeconomic standpoint. Urban growth is determined by the evolution of the world economic system and, in particular, by the globalisation of markets. This has generated increased competition, including competition between cities themselves. Since the end of the 1980s, cities have been responsible for between 50% and 80% of the GDP of most countries. In other words, they represent more than mere links in the global economy; they are, in fact, pivotal points.

Hence the principles which broadly underpin the Habitat 11 programme. In fundamental terms, public policies must promote the capital, housing, property and employment markets, with a view to improving the efficiency of urban management (living conditions, infrastructures, services, environment, etc.). This is not just desirable in human terms but also essential if urban productivity is to be improved. Many decision-makers at the meeting agreed that privatisation of services, partnerships involving the authorities, the community and the private sector, and decentralisation were all part and parcel of a new standard for good local governance.

Representatives of 'social' interests, on the other hand, were successful in focusing the debate on fundamental rights and principles, including individual and social rights. Indeed, these issues dominated the Conference and gave rise to the most difficult negotiations.

There were prolonged talks, for example, on the central issue of the right to a roof over one's head. The outcome was a commitment by governments to promote 'the full and progressive acceptance of the right to adequate shelter'. The NGOs had been hoping for a more clear-cut undertaking. Questions relating to the status of vulnerable groups, women's rights and their equal access to land, and protection against eviction, were also the subject of heated exchanges.

Perhaps the most important step forward, however, was the success of civil society representatives in sowing the seeds of a new idea - the 'right to the city'. This concept has been devised on the basis of research into more equitable and soundly-based development models to which local authorities are increasingly giving practical support. Thousands of individual experiences and issues were highlighted in Istanbul by NGOs and community groups. Thus, there is a mass of evidence that populations are capable of responding through local initiatives and of taking responsibility for improving their living and housing conditions. If this 'resource' is to be exploited to the full, urban politicians must develop a deeper understanding of the scale of micro-territories and local societies within cities. They also need to promote and coordinate their decision-making in a way which involves consulting and involving the local populations. In the modern era, this is the key to ensuring social cohesion.

Beyond Istanbul

There may have been a lot of new thinking on the basic principles, but there was no reference to financial undertakings in the Habitat 11 programme. On the latter issue, the international community was highly circumspect.

The World Bank took the initiative, announcing the launch of an 'urban compact', involving an additional $15 billion in loans for urban projects over the next five years. It also revealed that it would triple its aid to NGOs involved in the urban environment. Recent World Bank estimates suggest that just 0.2% to 0.5% of a country's GDP would need to be set aside for the poor to gain access to basic urban services.

As regards monitoring, the NGOs and local authorities won the right to sit on the Human Settlements Committee which will be responsible for implementing the habitat programme.

The most important points to emerge from Istanbul, however, were that local authorities were given both formal recognition, and a major practical role - in keeping with their current responsibilities. The habitat programme is, in fact, a powerful call for decentralisation and increased local autonomy, its action plan being built on the implicit principles of 'subsidiarily' and 'proximity'. To a large extent, the successful implementation of the programme will depend on the mobilisation of municipal politicians and officials - and on the policies they adopt at local level. The agenda for cities in the 21 st century that was adopted at the Rio Summit must now be fleshed out and become the future reference for action by local authorities, NGOs and citizens' associations. Finally, the importance of decentralised cooperation and the role of local councils in international cooperation have been reconfirmed.

Local authorities and their international organisations decided to form a worldwide coordinating group to continue structured dialogue with the international community and to guarantee that the Istanbul resolutions are followed up.

Some people predicted that Habitat 11 would be 'the revenge of the cities'. To quote P. Maragall, chairman of the Committee of the Regions, the conference at least provided the opportunity to build, and to give a wider audience to 'the voice of the United Cities within the United Nations'. That itself is a major step forward.

'A house to call my own'

Tackling violence against women

by Rosemary Okello

The author of this article is a journalist with the Nairobi-based Women's Feature Service (WFS) She contends that the Habitat 11 conference skirted around some of the issues affecting women city dwellers in Africa, such es violence and sexual abuse. Improving their lives, she argues, starts with a roof over their heads

The lofty ideals set during this year's UN Conference on Human Settlements in Istanbul meant little to African women like Catherine Kaberu.

As she recalls the misery of living on the streets of Nairobi, she is just happy now to have a safe, secure room for her family. 'I thought by running away from home and coming to Nairobi, I would find a better life" says Ms Kaberu. Instead, the streets became her home and her life was defined by the fear of violence against her. Her two children were born during that difficult period, following rapes. She cannot identify their father. There are an estimated 30 000 street people in Nairobi and Catherine Kaberu says that all street women and girls are regularly abused.

'Every day we had to look for a place to sleep and we bribed the watchmen to guard us.' Often it was the same watchmen, employed to guard office blocks in the city's central district, who took advantage of the women's desperate situation. Not even age could protect them says 63-year old Felista Nyambura, herself a veteran of the streets. 'I suffered all manner of humiliation,' she states, referring to ten years spent on the streets with her seven children. 'The watchmen would rape me if I refused to give in to them - after they had offered me a place to sleep for the night with my children. I am just so happy to be off the streets. I will never go back,' she states firmly.

The confidence of the two women comes from their new security as owners of simple one-roomed houses.

'Having a house to call my own is the most important thing that ever happened to me,' says Ms Nyambura as she explains how she ended up on the street after the piece of land her husband left in their rural home was taken over by her in-laws.

The two women are part of a group of 114 who have benefited from the Urban Destitute Programme, a project of the African Housing Fund which is involved in participatory community development with the homeless women of Nairobi.

Catalina Trujillo, the 'Women in Development' coordinator for the Habitat conference stresses: 'If a woman's place is in the house, we had better make sure she owns it.' These sentiments were supported in Istanbul by the conference Secretary General, Wally N'Dow: He stated: 'By conviction, by analysis and even by instinct, women's rights to ownership and inheritance of property is right. If Habitat II... does not also contribute to social progress by addressing some of the issues like property rights for women, then it will have failed.'

For the women of-Africa in particular, the most important thing that should have come out of Istanbul was an affirmation of their right to own and inherit property, and to security.

These issues affect most African women regardless of their status and they were presented to ministers concerned with shelter and settlements when they met in Johannesburg last year to prepare an African agenda for the Istanbul meeting.

Most African countries accept the theoretical premise that women must have access to land, credit and inheritance, and recognise that certain types of violence are targeted primarily at women. South Africa's President Mandela affirmed: 'When we talk about people-centred development, we should understand that the involvement of women is often the difference between success and failure.' Yet in reality, customary law and insensitivity to gender concerns continue to predominate. Unfortunately, when the African ministers adopted their declaration, the point on the "unencumbered access of women to credit and land ownership' appeared in only 20th place. And while forced evictions were highlighted in Istanbul, violence against women did not feature at all among the 'key priorities'.

Yet in parts of Africa these are major concerns affecting women every day. 'In South Africa, a women is raped every 83 seconds and in some areas, a girl can expect to be raped four times in her life,' says Emelda Boikanyo of the Johannesburg-based Women's Health Project. Idah Matou remembers how one Sunday morning in 1992, five men stormed into her shop in Alexandria township. They seized the day's earnings and anything else they could carry away before raping her 1 5-year old daughter. A few weeks earlier, they had called to demand protection money.

Violence in the home is also a growing problem. Mmatshilo Motsei, Director of Agisanang Domestic Abuse Prevention and Training, an NGO based in Alexandria, South Africa, says the problem is so pervasive, 'it must be raised as a national concern.' Habitat II turned a deaf ear on these women's concerns. This was not their forum. Shawna Tropp of the NGO Women's Caucus criticised those attending the conference who claimed that it was not about women but cities. 'Women live in cities,' she says and adds: 'By and large, human settlements are still very much seen in terms of bricks and mortar'. She calls for greater understanding of the role played by women, usually in an unpaid capacity, in the management of communities. 'Everything begins with having a house in a secure neighbourhood where the dignity of women is protected.'

Megacities

The megacity personifies human misery for many in developing nations. As agglomerations proliferate in the twenty-first century, the United Nations Population Fund's 1996 report - The State of the World Population - considers how one might go about remedying the ills of city dwelling.

The UNFPA's figures for urban growth make worrying reading. Over half the world's people will live in cities within ten years (3.3 billion out of a total of 6.59 billion). Between 1970 and 2020, the urban population will have risen by more than two billion - and 93% of these will be in developing nations. These increases will add to the strain of an estimated 600 million people already living in urban areas of developing nations without the resources to meet their basic housing and health needs.

Back in 1950, New York was the only city with more than 10 million inhabitants. Today, there are 14 in this category. Tokyo, which is home to 26.5 million people, is the largest. And by 2015, many others are expected to join the megacity 'club' - Djakarta (Indonesia), Karachi (Pakistan), Dhaka (Bangladesh), Delhi (India), Tianjin (China), Manila (Philippines), Cairo (Egypt), Istanbul (Turkey), Rio de Janeiro (Brazil), Lahore (Pakistan), Hyderabad (India), Bangkok (Thailand), Lima (Peru), Teheran (Iran) and Kinshasa (Zaire).

While the majority of the world's people will be living in cities by 2005, it will take a little longer for the 50% threshold to be crossed in the less developed regions. However, this is expected to happen before 2015. Looking specifically at Africa, the current estimates reveal significant regional variations. In Southern Africa the rate of urbanisation is 48%. The figures for North, West, Central and East Africa are 45%, 36%, 33% and 21 % respectively.

Expanding populations are likely to add to the widely reported list of horrors emanating from cities that are bursting at their seams. Problems include the collapse of basic services such as water and waste management, escalating social conflict, millions of urban children open to labour exploitation, sexual exploitation, environmental degradation, traffic congestion and environmental hazards such as increased air pollution.

On the other hand, the UNFPA report acknowledges that cities are also 'concentrations of human creativity and the highest form of social organisation'. It continues: 'Cities provide capital, labour and markets for entrepreneurs and innovators at all levels of economic activity'. Indeed, between 60% and 80% of developing countries' GNP is generated by their major conurbations. Social transformation occurs at a faster pace in urban areas. Thus, health indicators tend to be better, literacy is higher and there is more social mobility. And there are more opportunities for women. The city presents fewer obstacles for women's education and female city dwellers are less likely to be constrained by traditions which may stifle their creativity.

But harnessing this potential is no easy task. The final chapter of the UNFPA report, entitled 'Policies, strategies and issues for improving cities', argues that urban dwellers in developing nations have been badly affected by structural adjustment policies. These have resulted in the elimination of subsidies on food and other commodities, increases in school fees and job losses in the public sector. Cities will also be required to adapt to the 'mass global experience in decentralisation' involving the shifting of local decisions from central government to municipal authorities, parastatal bodies and the private sector.

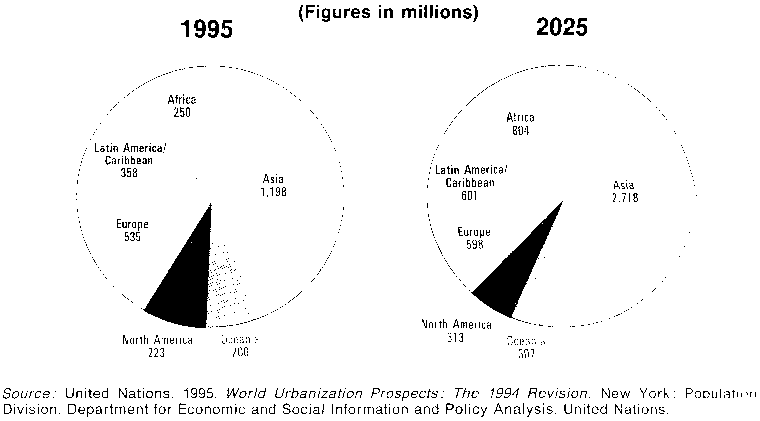

Regional distribution of urban population

Women - a priority

The report stresses the importance of improving education and health, with a particular focus on women. As Dr Nafis Sadik, who is Executive Director of the UNFPA, observes; 'If urban centres are to be made liveable, and the quality of life of the poorer members of society is to be improved, women should be given the chance to play their role in the process.'

The report reiterates the specific targets for improving the lives of women that were drawn up by the 1994 International Conference on Population and Development held in Cairo.

In the field of education, these include 100% primary school enrolment (for both girls and boys) by 2015, improving access for girls and women to secondary, tertiary and vocational education, and closing the gender gap in the primary and secondary sectors by 2005.

Other goals include a progressive reduction in infant and maternal mortality, making reproductive health services accessible to all through the primary health care system by 2015, greatly improved provision for family planning (allowing couples to make free and informed decisions on the number, spacing and timing of births) and providing better protection against sexually transmitted diseases.

The State of the World Population Report concludes: 'A successful urban future depends, as much as anything else, on engaging all members of the community - especially women and the poor - in a constructive political process.

There will have to be partnerships struck between governments, nongovernmental organisations, the private sector, and local and community organisations.

And global urbanisation will require that the international community - governments, NGOs and international institutions - act to exploit the potential of cities to improve the lives of the world's people and to establish the foundations of sustainable development in the 21st century.'

Lagos under stress

by Paul Okunlola

With a present population of some 7.5 million, the new millenium will propel Lagos to megacity status. The United Nations Population Fund predicts that 24 million people will live in the city by 2015, making it the third most populous conurbation on the globe. Whilst the donor community has supported urban projects in the past, tough times mean more reliance on 'bottom up' schemes backed by N60s and community-based groups.

When it began to rain in the small hours of Thursday 18 July 1996, residents of Lagos - Nigeria's largest city and economic nerve centre - merely stirred in their slumber. The gentle, but persistent showers, didn't rank among the heaviest downpours experienced by this coastal city, which gets rain on average for eight months in every year. Nor are Lagosians unfamiliar with spells of rain lasting up to seven days without break.

But by the time of the early morning 'rush hour', the traffic-laden streets of metropolitan Lagos were being swept with rampaging floods. Until well after noon, the city's social and economic life was at a standstill. Already difficult road conditions were rendered impossible for motorists, marooned at the wheel for hours. Exhausted school children eventually made it back home after spending the better part of the day in traffic. Crowds of commuters waited interminably at bus-stops for vehicles that never came.

The economic toll was expected to be heavy, with offices in both government and the private sector remaining empty all day. Commercial activities were put on hold as shops remained shuttered until well after noon. The communications network and electricity supply to key areas of the city were shut down for hours, to protect equipment. One state government official commented: 'It has never been so bad.' By the time the water receded and life had returned to normal, both government engineers and private sector consultants were in agreement: the main reasons for the flooding were illegal development along the natural courses of inner-city waterways, and the reduced drainage capacity of the overdeveloped metropolitan area.

Exploding metropolis

Both the flood itself, and the acknowledgement of the human limitations of the city officials, illustrate the frustrations that have attended the management of this exploding metropolis over the last three decades. In the months leading up to the July flooding, a major controversy erupted over plans to landfill the inland Kuramo lake in the highbrow Victoria Island district and develop it as a housing estate. This pitted state government officials and a firm of developers on the one hand, against a motley band of citizens groups, non-governmental organisations and concerned environmentalists on the other.

The unusual strength of local feeling against the project reflects growing fears that the island itself could be submerged. Five years ago, this was thought to be a remote prospect but today it is seen as a real threat, given the increasing frequency of flooding incidents and ocean surges along the coastal area.

More and more people are arguing that there is a correlation between the growing frequency of flooding incidents and the massive sandfilling activity that has taken place over the years. The Kuramo issue remains contentious but it is just one example of the wider dilemma facing the city's development planners. They have the daunting task of providing for legions of migrants to Lagos - whose swelling numbers are placing great stress on the failing infrastructure. The problem may be particularly acute in the Nigeria's largest city, but it reflects a wider trend of urbanisation in the country over the past half century, as the overall population has increased.

In 1921, Nigeria had just 18.7 million inhabitants. Current estimates put the population in the region of 103.5 million. And the growth in the proportion of urban dwellers has been equally dramatic. In 1931, fewer than 7% of the people lived in urban centres. The figure had risen to 10% by 1952,19% by 1963, 33% by 1984, and 42% at the last count, in 1991. Current figures suggest that there are now seven Nigerian cities with more than a million inhabitants and no fewer than 78 whose population exceeds 100 000.

The changing structure of the country's human settlement profile has been linked to broader economic and social changes. The situation has been exacerbated by the economic depression of the last two decades. Analysts have noted a trend of declining primary production in such areas as agriculture, mining, quarrying and exploitation of natural resources. This has resulted in greater attention being paid to secondary and tertiary economic activities - which are generally city-based. The figures illustrate the dramatic nature of the change that has taken place. In 1952, the ratio of primary to secondary/ tertiary economic activity, as measured in Nigeria's GDP, was 68:32. Four decades later, the ratio was 38:62.

According to World Bank consultant, Prof. Akin Mabogunje, the trend is exemplified by the expansion of a whole range of activities located in urban centres - large, medium and small-scale enterprises in manufacturing and construction, utilities, transport and communications systems, wholesale and retail outlets, hotels, restaurants, finance and insurance companies, and estate agencies. Then there is the whole range of government activity. Until 1991, Nigeria's huge federal bureaucracy was located in Lagos, operating alongside a state administration and some 15 local authorities. Add to this the major docks and airports of Lagos, and you get an urbanisation phenomenon which has, to say the least, been intimidating.

Lagos, which only occupies 0.4% of the country's land area, gains an extra 300 000 inhabitants every year on top of its natural growth rate. That the city is a 'pole of attraction' is hardly surprising. It is clearly the economic nucleus of the country, reputed to account for about 57% of total value added in manufacturing and about 40% of the nation's most highly skilled manpower.

Urban toll

The costs have also been high. Professor Poju Onibokun, a human settlements expert, enumerates these: grossly inadequate housing and infrastructure with millions dwelling in slums; social amenities under enormous pressure with a shortage of schools and poor health facilities; endemic crime and juvenile delinquency; the breakdown of traditional values, family cohesiveness and community spirit. The capacity of law enforcement institutions is also increasingly hampered by technological and resource limitations.

Of these ills, the shortage of housing and lack of infrastructure are seen as the most acute. This is borne out by a recent World Bank study which notes that:

- the quality of life and living conditions have deteriorated;

- economic production has plunged;

- the inadequate provision of infrastructural services has negatively affected the operations of most private sector investors, who now need to spend between 22% and 25% of their capital outlay on providing their own infrastructure.

Over 90% of the city's housing is provided by the private sector. But this has been handicapped in recent times by spiralling development costs and a general shortage of funds. New private housing has consisted largely of thousands of individual units, built mainly in areas of existing large scale developments. The authorities have made their own efforts to plug the gap and over the last 15 years, no fewer than 6000 hectares of marshland have been sandfilled and reclaimed in six separate development schemes (some of which have proved controversial). The Land Use Act of 1978 vested all urban land in the state authorities, although the administration of the legislation has not always proved satisfactory.

Public transport is another problem for Lagos residents. There is no integrated system of mass transport and the sector is essentially made up of hundreds of privately operated buses and a dwindling taxi fleet. Massive currency devaluations have meant that the purchase price of new vehicles has rocketed. Maintenance costs for the increasingly dilapidated fleet have also spiralled. As a result, the system is stretched to beyond its capacity and it is the commuters who bear the brunt.

Public sector spending obviously has an important part to play in maintaining urban structures. The downturn in international aid flows has, therefore, had a visible impact with decline in infrastructure provision and maintenance, leading to a less favourable operating environment for private investors.

In the past, Lagos has been a notable beneficiary of urban support programmes with multi-million dollar schemes for water supply, storm water drainage, and infrastructure. Most of these have been World Bank-led but the support of the European Union and its Member States in this area is also considered crucial.

On the positive side, adversity has proved a catalyst for greater community-based and NGO activity in environmental and human settlement issues over the last decade. This is a fresh approach, based on 'bottom-up' strategies, which should open up muchneeded new avenues to urban management in Nigeria more generally and in Lagos in particular.

A Eurocrat in Istanbul

by Gilles Fontaine

The author, a specialist in urban development, offers us his thoughts on the Istanbul conference. This event, he believes, was a landmark in the collective process of raising awareness which was begun at the Rio Conference on the environment.

14 June 1996 - last day of Habitat II

Night fell a long time ago. A feeling of hope permeates the hall. Most of the work is completed but there are still disputes over a few paragraphs of the text of the Habitat 11 Agenda. Some delegates have not slept for two days and they can be seen standing around, afraid they might fall asleep. The sense of fatigue increases further when, at midnight, the symbolic 'stopping of the clocks' (to permit a successful outcome of the final negotiations) is announced over the PA system.

At two in the morning, the wait has become almost unreal. It is virtually unimaginable that the Conference should come to nothing, after two years of intense work. Since Wednesday evening, the general atmosphere has been almost euphoric. Agreement has been reached on all the essential points within the allotted time and the Conference is already being heralded as another success story. All that remains to be done is to finalise the 'Istanbul Declaration', a four-page policy text broadly summarising the work of the Conference. The Conference would finally close about two hours later, amid general relief - but why the impasse?

Breaking new ground... and remaining steadfast

Some problems arose where they were least expected! To everyone's surprise, 'informal' working sub-groups had to be set up to discuss nuclear testing and anti-personnel mines! These themes were a far cry from the Habitat Agenda, but this sort of thing inevitably happens at major international conferences.

Other stumbling blocks appeared without any real warning, when some delegates attempted to renegotiate the conclusions of the Beijing and Cairo conferences. The negotiators had to stand firm on two counts. The hard-won recognition of women's rights needed to be defended all over again. And, more importantly, the attempt in Istanbul to reopen the debate on everything that had been gained at previous conferences had to be avoided. The European Union's negotiators took an aggressive stance on both these issues.

The fact that so much negotiating effort is expended is a good illustration of the political significance governments attach to the topics debated on such occasions. A conference may be seen as resembling the proverbial half-bottle of water - some regard it as half empty and others as half full. One's viewpoint depends on one's expectations - and much disappointment is caused by a misunderstanding of how such conferences operate.

Meeting the delegates

Although I am no anthropologist, I think I was able to identify three major groups of participants. First, there were the 'negotiators', who have built up a common language from conference to conference. I was surprised at the extent to which reference was constantly made, in the negotiating groups, to the 'Languages' of Rio, Copenhagen or Beijing. This is not just a question of vocabulary or syntax, but represents a genuine revolution in thought at international level.

The second group, to which I myself belonged, was made up of national and international officials. These are the people who, to a greater or lesser extent, prepare the conference. They then attend it and, ideally, write a mission report on returning to their offices (bemoaning the fact that few people will read their words of wisdom !)'These delegates tend to offer the harshest judgments. A common refrain is: 'We have long argument about words in parenthesis in a huge document that no one will ever read!'.

The third group, which nowadays is the largest, consists of representatives of so-called civil society. Since Rio, every United Nations conference has seen the parallel organisation of an NGO Forum, and the latter's influence has constantly increased. At Beijing, the authorities banished the NGO Forum to a site 60 km from the capital, but Istanbul welcomed it with open arms on the same footing as the 'Cities Summit' and the meetings of researchers and industrialists. A more fundamental development was the invitation to NGOs and local authorities to take an active part in the working groups and at meetings. This was a 'first' in international conference history and I was struck by the motivation and competence of many of the participants, as well as by the ease with which they have adapted to the information society. Gone are the days when addresses are exchanged on scraps of paper, accompanied by the ritual 'We must keep in touch!'. These days, your business card must include your Internet Email address. Contacts are organised through networks connected to databases, and people swap CD ROMs with each other.

What did Habitat II achieve?

The 'official' end most visible result of the Conference was obviously the adoption of the Habitat Agenda - the final fruit of long hours of work within the national committees set up for the occasion. This document, over a hundred pages in length, contains a 'World Action Plan', accompanied by the 'Istanbul Declaration'.

What is not so well-publicised is the fact that many countries - including a number of ACPs - took the opportunity to publish their own national reports containing individual action plans. The amount of preparation that went into these reports revealed a high degree of motivation.

Having looked at them more closely since, I have gained a somewhat better understanding of the months of work put in tens of thousands of people across the world. This reassures me that the majority of state participants will monitor the Habitat 11 follow-up very closely.

One has to recognise that the mere adoption of a text, however significant it may be, cannot be regarded as a magic formula which will change the face of the world overnight. To the impatient among us who want everything straight away, and to unrepentant sceptics, I would say this. In environmental matters there are two major periods in our recent history - the period before Rio and the period after Rio. The Rio meeting, and each subsequent conference, have been milestones in a long, coherent process of collective reflection and growing awareness. Istanbul did, in fact, keep its promises: the right to adequate shelter is now recognised internationally as the fundamental right of every human being.

The exploding city

by Stephane Yerasimos

Istanbul. Ten million inhabitants - with double that number expected in 20 years time. Financial irregularities, a chaotic house-building sector, a lack of infrastructure and rampant speculation. One needed to look no further than the host city to find the key issues facing the Habitat Conference.

Istanbul is a city steeped in history. It is also one of the Third World's biggest conurbations. Over the last 16 centuries, it has been the capital of two great empires - the Byzantine and the Ottoman - resulting in a rich legacy of monuments and a historic centre on a par with that of Rome. From the Middle Ages to the beginning of the modern era, it was regarded as Europe's largest city. On the eve of the Second World War, it had a population of one million, but that figure has now multiplied tenfold. Almost half of its ten million inhabitants are living on a knife edge, and many are in 'illegal' housing.

The first big transformation of the city came in the middle of the 19th century when the Ottoman authorities opted for westernisation and embarked on an extensive management programme. By the time the Empire collapsed in 1922, much of the ancient fabric - and traditional housing - of the city had already been lost. Under the new republic, the capital was transferred to Ankara, and the authorities stepped up their efforts at modernisation. In 1937, Ataturk gave Frenchman Henri Prost, a city planner who had helped preserve the old centres of a number of Moroccan towns, the job of devising major public works in the heart of the old city. The infrastructure was also updated and taken together, these works (which were completed during the 1950s) transformed the old walled city and its ancient suburbs (Galata and Uskudar) into a modern aggLomération, interspersed with ancient monuments.

Mass immigration

Unlike the colonial powers who attempted to preserve the traditional character of old city centres around the Mediterranean rim and in the rest of the Islamic world, the desire of successive Turkish governments to modernise the country resulted in the disappearance of most of Istanbul's ancient fabric, and the city no longer has a compact area of old districts.

The transformation of the city centre was matched, after the Second World War, by an explosion of building on the outskirts - a phenomenon characteristic of Third World countries. Improved sanitation and hygiene standards led to a natural population increase of between 2.5% and 3% per year. Meanwhile, the modernisation of agricultural practices caused a mass rural exodus. Marginalised in both economic and social terms. the people who flooded into Istanbul soon over whelmed the resident population. Today, the bulk of the people living in the city have rural origins.

The new residents began by occupying the edges of the old quarters and taking over the open spaces which remained after the ravages of an earlier fire. They then began to settle in ever-increasing circles around Istanbul, establishing the first gecekondu districts (groups of huts constructed overnight). These have been incorrectly described as shanty towns. In fact, most buildings are permanent structures and they rapidly develop into multi-storey dwellings. Most of the land on which these illegal buildings have sprung up was originally privately owned. But the elected multi-party government in power at the time was quick to spot the electoral possibilities in these areas. Each district was a reservoir of potential voters and, on the eve of each election, the parties in power would distribute property titles to the illegal occupants. They, in turn hastened to consolidate and increase their assets. This explains the emergence of increasingly densely populated districts without infrastructure during the 1950s and early 1960s

Industrialisation, and the arrival in the city of people who used to be rural landowners (driven out by the new market economy) later created a demand for housing which the normal market was unable to meet. This has given rise to a new phenomenon of urban marginalisation, involving the illegal division of land into plots. The system involves the purchase of agricultural properties by developers and speculative builders. These are divided into small plots and resold, quite legally, to purchasers - who then build unauthorised structures in contravention of the normal planning rules. Often, benefiting from political alliances, the developers take control of these districts and 'convert' the votes of the people living there into cash, in return for urban investments. This enables them to consolidate their power and increase the value of their remaining stock of plots.

An uncontrolled population increase

Finally, a third phenomenon, linked to the growth of a middle class, began to occur in the mid-1980s, when building cooperatives came into being. Their predecessors were the corporate associations which grouped together public officials (beginning with the army and the police). These developed into ad-hoc associations enabling a group of developers to tap people's savings, thereby dispensing with the need for loans in a country where chronic inflation makes credit prohibitive. Several thousands of dwellings are often constructed at the same time, in the form of tightly packed, multiple-occupancy blocks. The requirements of multi-storey construction mean that these buildings are of acceptable quality, but the related infrastructures are sorely lacking. Entire districts are built 'in the wilds' without any infrastructural investment by the developers or local authorities.

The city is continuing to expand, without reference to any development plan. The fifteen or so major urban schemes drawn up since the 1950s have all remained in desk drawers and the only significant construction work has been on roads (notably bridges and ring roads). These generate further uncontrolled population increases on the outskirts of the city.

Although the natural rate of demographic growth is slowly declining - it has just dropped to under 2% per year - the most recent census (in 1990) reveals that Turkey now has more people living in its cities than in its rural areas. Yet the statistics also show that half of the country's people are still involved in agriculture. Given the continuing natural growth, and the fact that in semi-industrialised countries, the rural population tends to settle at around a third or even just a quarter of the total, we can assume that the drift to towns and cities will continue for the next 30 or 40 years. This trend will affect all Turkish towns and cities, be they large, small or medium-sized. But Greater Istanbul, where the majority of the country's economic and social activity is concentrated, is set to experience a doubling of its population within the next twenty-five years.

Dilemma for urban planners

The problem caused by demographic changes is exacerbated by economic constraints. For a number of years now, Turkey has suffered a high (albeit stable) inflation rate of about 70% per year. This situation discourages investment in industry, and makes people take refuge in ownership of land that they can build on. Land has thus become the target of speculation by people in all social classes. Against this background, it is virtually impossible to regulate the use of land - something which must be at the heart of any urban-development programme. An alternative is to discuss the possibility of developing a social consensus involving a more liberal approach to property speculation, recgnising that land is a source of revenue at all levels. This might entail releasing central and local authorities from any responsibility to provide services or other infrastructural investment.

In the present circumstances, however, any scheme to redevelop Istanbul effectively would seem doomed to failure. The only intervention which might succeed would be at the 'cleaning-up' stage - coming in after the construction of the dwellings under the conditions described above. It is only once the new inhabitants' dream of having a roof over their heads is realised that they come face to face with the harsh daily realities of living in a self-built city of nearly ten million people. They may then be prepared to make some sacrifices in order to improve their living conditions. The moment when harsh reality replaces emotion, is the only time the urban planner has the slightest chance of being listened to.

Adequate housing in the EU: rights and realities

by Misia Coghlan

There are 2.7 million homeless people in the European Union and many millions more are badly housed. But the EU is said to be lagging in taking measures to provide adequate housing - one of the internationally recognised human rights. An expert from a leading campaign group for the homeless explains.

Rights

In the weeks and months leading up to the Second United Nations Conference on Human Settlements (Habitat II), much argument and debate centred around the existence of the right to adequate housing. The legal basis of this right was challenged by a handful of delegates and the arguments continued right through the Conference itself. The outcome is that the final Declaration includes a reaffirmation of states to a 'commitment to the full and progressive realisation of the right to adequate housing as provided for in the international instruments.' (see first box)

The political impact of Habitat II as the culmination of the recent series of UN Conferences has been disappointing. The Istanbul Conference was originally heralded with the catch-phrase 'housing for all'. In the course of the preparatory process, this was watered-down to become 'shelter for all' and, as has been seen, the wording of the final Declaration simply refers to existing international commitments and allows for the 'full and progressive realisation of the right.' This of course begs the question of how such a right was ever supposed to have been achieved other than 'progressively' and how meaningful such a commitment can be in the absence of parallel undertakings as to implementation and enforcement. In short, very little has been achieved in progressing international commitment to the realisation of the right.

The right to adequate housing has in fact been recognised for some time now by the Member States of the European Union, all of whom have ratified the 1966 International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (the most important legal basis of housing rights found in international law). Under article 11(1), the parties to the Covenant recognise, 'the right of everyone to an adequate standard of living for himself and his family, including adequate food, clothing and housing...'

The concept of 'adequacy', it is generally acknowledged, is determined at least in part by social, economic, cultural and climatic factors. Adequate housing can be understood as including the following components: legal security of tenure, affordability, habitability, accessibility, location and availability of services, materials, facilities and infrastructure.

It hardly needs pointing out that commitments in international law, whether legally binding or not, remain statements of intent and are of limited practical use unless accompanied by a comprehensive legislative framework in domestic law which will secure both the access to the right as well as providing enforcement mechanisms. What, then, is the reality ? Has the right to adequate housing been enacted into national legislation and, most importantly, is the right actually being respected across the European Union?

Realities

FEANTSA, the European Federation of National Associations Working with the Homeless, has been conducting the European Observatory on Homelessness with the support of the European Commission since 1991. FEANTSA's research findings have increasingly demonstrated both the extent and the gravity of the housing crisis in Europe: in what is one of the wealthiest subregions of the world, a large and growing group of the population is being excluded from adequate housing. (see box on next page)

Moreover, FEANTSA's 1995 transnational research report (Home/essness in the European Union) has found that the right to housing does not exist in any Member State as a legally enforceable claim. Although the right is recognised in the constitution of several Member States, this remains a statement of intent and does not create any entitlement. Other Member States have adopted a different approach - housing legislation in the United Kingdom, for example, does create an obligation on the local authorities to provide housing for those homeless people assessed to be in priority need and found to be unintentionally homeless. There is no sign of convergence in the ways EU Member States address the right to housing and housing exclusion in their national legislation.

The right to housing is not addressed in EU legislation as a legal principle and Member States have exclusive competence to deal with housing issues themselves. There is thus no overall European housing policy, nor is there yet any European policy on homelessness. FEANTSA has, however, identified common trends throughout Europe which have contributed to the escalation of homelessness and the lack of adequate housing provision.

The overall European trend has been an increased reliance on the competitive market to meet all housing needs, with an unwillingness on the part of government to commit public resources to assist lower income groups, who are therefore confronted with the limited choice available to them on the open housing market.

The supply of housing has been undergoing change throughout Europe. In all countries, owner-occupation is on the increase, with tax relief generally being offered as an incentive. The private rented sector, on the other hand, has continued to decline. Social housing has generally suffered from cuts in funding. The result is that there is a shortfall in the supply of affordable housing for rent and rents have become correspondingly higher. It is clear that the competitive housing market cannot and will not meet the needs of the increasing numbers of people without the resources to afford market rents.

The type of housing required has also changed: demographic trends have meant that households are getting smaller but more numerous - thus, there is a need for more but smaller dwellings.

The problem has been exacerbated by the lack of an overall strategy either at European level or, indeed, often at national level, to meet the realities of structural changes on the labour market. Indeed, in some countries, the increase in long-term unemployment has been accompanied by an erosion of social protection systems. Faced with escalating demand for longterm welfare assistance, the authorities have often responded by tightening up on eligibility criteria in an attempt to cut or limit benefit payments, with shortterm palliative measures to deal with emergency cases. Thus, increasing numbers of people living on or under the poverty threshold, coupled with the deregulation of the housing market, have led to severe housing stress and increased vulnerability to homelessness.

Finland sets an example

Finland is one EU country tackling the housing problem. In 1987, the International Year of the Homeless, the Finnish government announced its intention to eliminate homelessness. At that time, the number of homeless people was put at close to 20 000. The programme for the development of housing set the objective of making 18 000 homes available for the homeless over a period of five years. Special funds were set aside in the national budget to permit the local authorities and other organisations to purchase housing for the homeless. State loans for the construction of housing for rent were made available to municipalities with a large homeless population. In under ten years, the number of homeless people in Finland has been reduced to half what it was in the mid-1980s. Finland now enjoys a comprehensive system of carefully targeted housing supply, housing subsidies, benefits and allowances and housing is seen as an integral part of a multi-dimensional strategy to combat poverty.

For one in twenty citizens of the European Union, the criteria which, as a whole, constitute adequate housing remain inaccessible. Yet at Istanbul, the EU voiced its determination to make an important and constructive contribution to the implementation of the Habitat objectives. This included an acknowledgement that increased attention should be paid to people living in poverty and that appropriate action should be taken by governments at all levels.

The European housing ministers were due to meet informally in Dublin, on 24 and 25 October of this year, specifically to tackle the question of 'housing for socially excluded people'. The time has come to devise and implement coherent strategies to prevent housing exclusion for low income groups. The market has neither the ethics nor the long-term planning capacity to do this; it remains the responsibility of the state. It can only be hoped that the housing ministers will recognise this and agree on the necessity of protecting housing as a product and as a service from the competitive market, at least for vulnerable groups. The housing ministers have been holding informal meetings since 1989. This year's meeting provides the opportunity, particularly in the light of the Habitat II debate, to exchange information on effective measures to help low income groups access and maintain a home. The result should be the drafting of a number of concrete goals to be achieved within a realistic time-scale.

Homelessness in Europe is not on the scale seen in other regions of the world - with the development and reinforcement of effective preventive policies, based on proven and cost-effective welfare models existing in some Member States, the housing crisis can still be contained. In short, where there is a political will, there is a way. Europe has the potential to serve as a model of good practice to the rest of the world and should do so, more especially in the light of all that was - and wasn't - achieved at Istanbul.

References

Is the European Union Housing its Poor ? Dragana Avramov, Catherine Parmentier and Brian Harvey, FEANTSA, Brussels 1995

Homelessness in the European Union, Dragana Avramov, FEANTSA, Brussels 1995

The Invisible Hand of the Housing Market, Dragana Avramov, FEANTSA, Brussels 1996

Cities of the Third World

by Francis Cass

In ten or so years' time, more than half the world's population will be living in built-up areas and, according to UN figures, by 2025 nearly two thirds of us will live in towns and cities. This is not a complete surprise - over the last few decades, the ratio of city dwellers to rural people has consistently moved in 'favour' of the former. In 1950, 29% of people were city dwellers. Since 1985, the urban population has exceeded 40% of the global total.

Today, we are witnessing an acceleration in demographic growth, especially in developing countries. Of the 2.6 billion people who currently live in towns, 1.6 billion live in the world's least developed regions. By 2025, the urban population of the Third World will have risen to 3.2 billion, out of a global urban population of just over 4 billion. On the basis of these figures, it is estimated that the number of urban dwellers in developing countries is increasing by approximately 150 000 people each day! In Cape Town in South Africa, for example, as in many towns and cities of the Third World, this demographic explosion can actually be seen happening. All you need to do is drive regularly along the N2 motor way - which passes through the shanty towns of Khayelitsha and Guguletu - to see how, week by week, the makeshift dwellings are spreading - gradually expanding to every available plot of land. The same scene is repeated in all of Africa's large towns. In Coté d'lvoire, the population of Abidjan rises by 400 inhabitants a day on average. In Gabarone, the capital of Botswana, whose population was barely 3000 at the time of independence in the 1960s, the population is increasing by 18% each year and today 160 000 people live there. Such growth is often accompanied by widespread indifference on the part of local authorities. Such indifference is due, in particular, to a shortage of financial resources, but it also reflects an absence of political will to do anything to tackle the problem.

Demography and poverty